Module 2: Classification of Aquaculture Production Methods

Summary / Description Text

This module addresses the classification of aquaculture production methods according to different criteria. Production systems are classified by aquatic environment (freshwater, brackish water, marine), by water circulation (open, semi-closed, closed and recirculating systems), by production technique (net cage, raft, pond, concrete pond, earthen pond, tank, park) and by integration status (integrated systems such as rice–fish, duck–fish, chicken–fish, aquaponics and traditional systems). The advantages, limitations and environmental impacts of each system are explained with examples. The contributions of integrated production systems to resource efficiency, ecological sustainability and rural development are emphasized.

Keywords: freshwater, brackish water, marine, open system, closed system, recirculation (RAS), integrated systems, aquaponics, sustainable production.

Learning Outcomes

- To learn the criteria for classifying aquaculture production methods.

- To understand the advantages and disadvantages of different systems.

- To comprehend the ecological and economic contributions of integrated aquaculture systems.

- To explain the importance of recirculating systems in sustainable production.

Presentation File

1.2. Classification of Aquaculture Production Methods

There are various ways to classify aquaculture production methods. Aquaculture production methods are classified according to the water environment in which the culture is conducted, the circulation of water within the system, the production technique used, and whether the production is carried out as integrated systems.

1.2.1. Classification by Water Environment

1.2.1.1. Aquaculture Conducted in Freshwater

Freshwater aquaculture is defined as the production of aquatic organisms such as fish, crabs, and shrimp using freshwater resources, carried out in inland waters, ponds, and closed systems (Ahmad et al., 2021). In Turkey, many aquatic species are raised in freshwater. According to Turkish aquaculture statistics, the most commonly farmed species in the country are Rainbow Trout, Trout (Salmo sp.), and Mirror Carp (TURKSTAT, 2024). Freshwater aquaculture is reported to occur predominantly in Asian countries, particularly in China (Li & Liu, 2019; Boyd, 2009). Common fish species raised in freshwater include carp, catfish, and trout (Boyd, 2009). In addition, freshwater is also suitable for the culture of crustaceans, mollusks, and aquatic plants (Boyd, 2009). Table 1 presents the most produced aquatic species and their quantities in Turkey’s inland waters.

Table 1. The most commonly produced aquatic species and their quantities (tons) in inland waters of Türkiye (TURKSTAT, 2024).

| Most Commonly Farmed Species in Inland Waters of Türkiye | |||||||

| Years / Species | Trout (Rainbow trout) (ton) | Trout (Salmo sp.) (ton) | Carp (ton) | Sturgeon (ton) | Tilapia (ton) | European catfish (ton) | Frog (ton) |

| 2014 | 107533 | 450 | 157 | 17 | 32 | – | 50 |

| 2015 | 100411 | 755 | 206 | 28 | 12 | – | 43 |

| 2016 | 99712 | 1585 | 196 | 6 | 58 | – | 44 |

| 2017 | 101761 | 1944 | 233 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 43 |

| 2018 | 103192 | 1695 | 212 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 49 |

| 2019 | 113678 | 2375 | 203 | – | 6 | 121 | 43 |

| 2020 | 126101 | 1804 | 173 | 14 | 13 | 92 | 39 |

| 2021 | 134174 | 1558 | 171 | – | 6 | 84 | 49 |

| 2022 | 144347 | 1302 | 293 | 1 | – | 95 | 25 |

| 2023 | 154991 | 1440 | 216 | 1 | – | 79 | 31 |

1.2.1.2. Brackish Water Aquaculture

Brackish water forms in transitional zones such as streams, lagoons, estuaries, and coastal areas where freshwater mixes with seawater. Salinity in brackish water ranges between 0.5–30 ppt (Ahmed & Thompson, 2019). With the use of different aquaculture systems in these brackish water sources, various aquatic products such as fish species, mollusks, and shrimp can be produced (Anyanwu et al., 2007). Tilapia species, which are widely preferred in aquaculture production, are suitable for cultivation in brackish waters (Carmo et al., 2025). For example, the Nile Tilapia, although an efficiently farmed species in freshwater, can also be raised in brackish water environments with salinity up to 20% (El-Sayed, 2019). In addition, species such as mullet, tarpon, catfish, mussels, oysters, and periwinkles can be produced in brackish waters (Anyanwu et al., 2007). Table 2 lists some aquatic species suitable for production in brackish water zones (Anyanwu et al., 2007).

Table 2. Aquatic Species Suitable for Production in Brackish Water Zones (Anyanwu et al., 2007)

| Common Name | Species |

| Mullet | Liza falcipinnis, Liza grandisquamis, Mugil cephalus, Mugil bananensis, Mugil curema |

| Tarpon | Megalops atlanticus |

| Tilapia | Sarotheron melanotheron, Tilapia guineensis |

| Catfish | Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus, Bagus bayad, Bagus domae |

| Grunter (Snapper) | Lutjanus goreensis, Lutjanus aegenis |

| Ladyfish / Elops | Elops lacerta |

| Pomadasys (Grunt) | Pomadasys jubelini, P. peroteti, P. rogeri |

| Shrimp | Penaeus notialis, Penaeus monodon |

| Periwinkle (Marine Snail) | Tympanotonus fuscatus, Tympanotonus radula |

| Whelk (Marine Snail) | Thais coronata, Pugillina morio |

| Bloody Cockle (Mussel) | Anadara (Senilia) senilis |

1.2.1.3. Aquaculture Conducted in Saltwater

Mariculture is a type of aquaculture carried out to produce various fish species, aquatic plants, and shellfish in natural marine environments or in systems such as nets, cages, tanks, and canals, enabling the cultivation of seaweeds, mollusks, and many fish species (Laird, 2001). Table 3 also presents aquatic organisms suitable for cultivation in saltwater.

Table 3. Aquatic Species Cultivated in Saltwater (Laird, 2001)

| Group | Production Regions |

| Seaweeds (Red Algae) | Indonesia, China, Japan, Korea, Philippines |

| Seaweeds (Brown Algae) | China, Korea, Japan |

| Seaweeds (Green Algae) | Japan, Korea, Philippines |

| Shellfish — Oyster | China and France |

| Shellfish — Mussel | Europe, Far East, India, and coasts of North & South America |

| Shrimp — Penaeid | Coasts of South and Southeast Asia, and South America |

| Fish — Salmon | Chile, Canada, Australia, Norway, Scotland, New Zealand |

| Fish — Rainbow Trout | Chile |

| Fish — Milkfish | Indonesia, Philippines, Taiwan |

| Fish — Flatfish | Japan, France, Spain, Portugal |

| Fish — Seabass | Greece, Turkey, Spain |

| Fish — Coral | Japan |

1.2.2. Classification According to Water Circulation in the System

Open systems are those in which aquatic organisms are raised in water environments such as seas and lakes, and where the used water is returned to the source, with wastewater treatment being provided naturally by the water flow (Ahmad et al., 2021). Examples of these systems include cage systems, raft systems, pond areas, and parks.

In semi-closed systems, water obtained from natural sources is supplied to ponds or canal systems, and after the culture process, the resulting water returns to the source (Ngo et al., 2017). Figure 1 shows an example of a semi-closed system (Ngo et al., 2017).

In raceway systems of aquaculture, the water is channeled through canal systems positioned in the flow direction of wells, rivers, or streams, and the culture process is carried out in the running water (Ahmad et al., 2021). After the culture process, the resulting wastewater is treated and discharged back into the water source. It is stated that in flow-through systems the hydraulic retention time is less than one hour (Ngo et al., 2017).

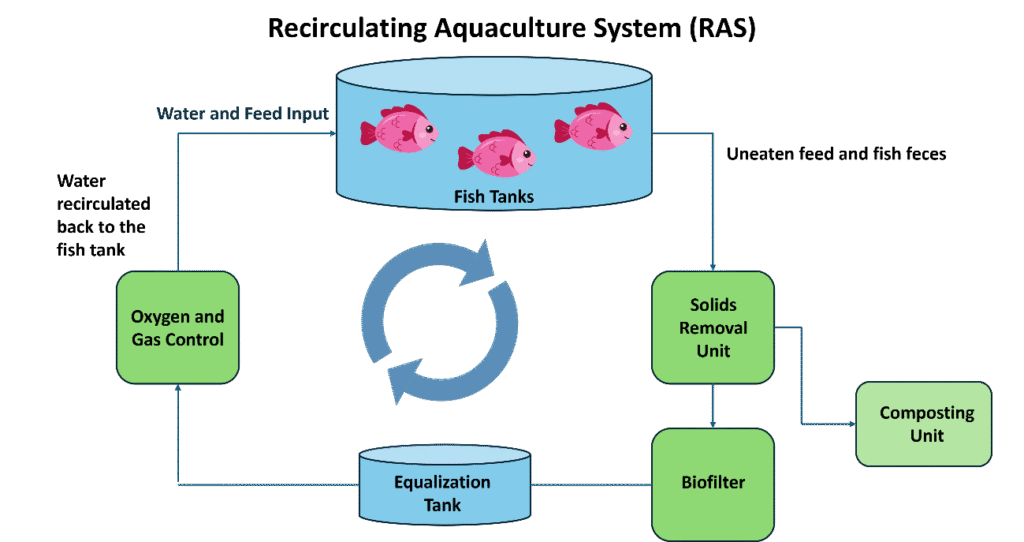

In closed systems, aquaculture refers to the cultivation of aquatic organisms in a controlled environment where water is continuously reused in a closed loop (Uğural et al., 2018). By adding wastewater treatment units for the purification of the water used, Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) are formed. The recirculating aquaculture system is an advanced and sustainable aquaculture system implemented in closed units. In closed systems, the water used for cultivation circulates within the system with the addition of a limited amount of external water. Compared to pond and cage-based aquaculture techniques, these systems represent an environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative. They are more advantageous than other forms of aquaculture due to their smaller space requirements, far more efficient use of water, and the ability to control water quality and temperature to ensure more efficient processes (Ustaoğlu Tırıl & Dalkıran, 2005).

1.2.2.3.1. Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS)

A recirculating aquaculture system essentially consists of components such as a fish tank, mechanical filtration unit, biological filtration unit, pump, UV unit, aeration unit, oxygen injection unit, feeding unit, and monitoring system (Bregnballe, 2015). In Turkey’s RAS facilities, the production of aquatic organisms such as Ornamental Plants, Ornamental Shrimp, Whiteleg Shrimp, Shrimp–Kuruma, Shrimp–Green Tiger, Trout–Abant, Whiteleg Shrimp, Meagre (Trança), Goldblotch Grouper (Sarıağız-Granyöz), Seabass, Meagre–Kötek, Red Seabream (Mercan–Fangri), Rainbow Trout, Dentex (Sinagrit), Gilthead Seabream (Çipura), Common Two-banded Seabream (Sivriburun Karagöz), Antennae Coral–Blue Spotted Grouper (Mercan–Antenli–Mavi Benekli), Dusky Grouper (Lahoz–Grida), and Amberjack (Sarıkuyruk–Avcı) is carried out (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025). In Turkey, RAS facilities are located in the provinces of Antalya, Balıkesir, Bolu, and Muğla (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

Since the water initially used in these systems is treated and recirculated back into the system, water consumption and wastewater discharge are lower than in other systems. However, due to the mechanical equipment and units used, energy consumption is high (Bernal-Higuita et al., 2023).

Figure 2 shows the schematic of a recirculating aquaculture system.

1.2.3. Classification by Production Technique

1.2.3.1. Net Cage

The net cage system consists of open systems applied in lakes, ponds, rivers, seas, and oceans, designed in circular, square, or polygonal shapes. In general, there are many components that make up a cage system. A typical cage system includes netting material, frame/yoke, service platform, mooring systems such as rope–anchor–buoy, flotation equipment, and auxiliary equipment such as feeders and safety gear (Dikel, 2005). Figure 3 shows an example of a net cage aquaculture system.

The netting material used in net cages varies depending on the characteristics of the fish species to be cultured. For fish farming to be efficient with the net cage system, the choice of netting material should be made by considering parameters such as lightness, resistance to floating objects, durability for harvesting, and resistance to wave movements (Dikel, 2005).

There are also important considerations to ensure that aquaculture in cage systems is carried out properly. For example, the water depth at the site where the system is established should be at least 5 meters to prevent the fish from being affected by temperature changes in the water; the selected site should be in a wind-protected area and preferably far from human settlements (Dikel, 2005).

A wide variety of species can be produced in cage systems. In aquaculture facilities in Turkey, aquatic organisms produced in cage systems include Rainbow Trout, Black Sea Trout, European Seabass, Gilthead Seabream, Goldblotch Grouper (Sarıağız-Granyöz), Common Two-banded Seabream (Sivriburun Karagöz), Red Seabream (Mercan-Kırma), Dentex (Sinagrit), Bluefin Tuna (Orkinos-Mavi Yüzgeçli), Brown Meagre (Eşkina-Mavruşgil), Meagre (Minekop-Kötek), Red Seabream (Mercan-Fangri), Antennae Coral–Blue Spotted Grouper (Mercan-Antenli-Mavi Benekli), Red-banded Seabream (Mercan-Kırmızı Bantlı), White Seabream (Sargoz), Royal Dentex (Egeli), Dusky Grouper (Lahoz-Grida), Turkish Salmon, Carp (Mirror and Scaled), Red Seabream (Mercan-Fangri), Meagre (Trança), Striped Seabream (Mırmır), Amberjack (Sarıkuyruk-Avcı), Sturgeon (Karaca), Hybrid Bester Sturgeon (Mersin-Hibrit Bester), and Large-spotted/ Mountain Trout (Alabalık-Büyük Benekli-Dağ Alabalığı) (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

In Turkey, aquaculture facilities with cage systems are located in the provinces of Adana, Adıyaman, Afyonkarahisar, Ankara, Antalya, Artvin, Aydın, Balıkesir, Bingöl, Bitlis, Burdur, Bursa, Çanakkale, Denizli, Diyarbakır, Elazığ (mainly), Erzincan, Erzurum, Gaziantep, Gümüşhane, Hatay, Isparta, Mersin, Istanbul, İzmir, Kastamonu, Kayseri, Kırşehir, Kocaeli, Konya, Malatya, Manisa, Kahramanmaraş (mainly), Muğla (mainly), Ordu, Rize, Sakarya, Samsun (mainly), Sinop (mainly), Sivas, Tokat (mainly), Trabzon, Tunceli, Şanlıurfa (mainly), Uşak, Van, Yozgat, Bayburt, Karaman, and Batman (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

1.2.3.2. Raft/Rope

Another example of an open system is the raft system, where mussel cultivation is carried out on ropes suspended from the raft structure. The system basically consists of wooden poles, floats, and ropes where mussels are grown. Anchors are used to fix the raft structure to the seabed (Çelik, 2006). Mussel farming is generally carried out with the raft system. In Turkey, the aquaculture products produced with the raft system are Mediterranean Mussels — Black Mussels (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025). Facilities using the raft system are located mainly in Balıkesir, Bursa, Çanakkale, İzmir (mainly), Muğla (mainly), Sinop, and Yalova provinces (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025). Figure 4 presents an example drawing for the raft system (Çelik, 2006).

1.2.3.3. Pond Area

This is a type of aquaculture production carried out in freshwater sources such as natural or artificial ponds (Bernal-Higuita et al., 2023). From an environmental perspective, pond area culture carries risks due to its high water consumption and the generation of large amounts of wastewater (Bernal-Higuita et al., 2023). Species commonly raised in pond areas include carp, trout, tilapia, and catfish (FAO, 2025a).

In Turkey’s pond areas, species such as Carp (Mirror and Scaled), Catfish, Crayfish, and Rainbow Trout are cultivated (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025). In Turkey, pond areas are located in the provinces of Adıyaman, Aydın, Bursa, Çanakkale, Edirne (mainly), Eskişehir, Hatay, Isparta, Nevşehir, Samsun, Siirt, Sinop, Tekirdağ, Şanlıurfa, Uşak, and Karaman (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

1.2.3.4. Concrete Pond

Pond systems are structures that create an artificial environment for the production of fish. Fish production ponds are classified into three different types: concrete ponds, earthen ponds, and plastic tanks (Atay, 1986). Pond sizes vary depending on many parameters. Analyzing parameters such as the climate characteristics of the location where the pond will be built, land structure, volume calculation according to the water to be used, the species of fish to be produced, the cultivation method, and economic conditions is important for determining appropriate pond sizes (Sedgwick, 1978; Atay, 1986).

In Turkey’s facilities practicing concrete pond aquaculture, aquatic species produced include Rainbow Trout, Sturgeon–Common Two-banded (Mersin–Sivriburun), Siberian Sturgeon (Mersin–Sibirya), Sturgeon–Karaca, Aquarium Fish, Doctor Fish, Ornamental Plants, Black Sea Trout, Carp (Mirror and Scaled), Turbot, Gilthead Seabream, European Seabass, Siberian Sturgeon, Karabalık–Dwarf Catfish, Doctor Fish, Medicinal Leech, Goldblotch Grouper (Sarıağız–Granyöz), Meagre (Minekop–Kötek), Red Seabream (Mercan–Kırma), Red Seabream (Mercan–Fangri), Dentex (Sinagrit), Meagre (Trança), Red-banded Seabream (Mercan–Kırmızı Bantlı), Antennae Coral–Blue Spotted Grouper (Mercan–Antenli–Mavi Benekli), Dusky Grouper (Lahoz–Grida), Spirulina, Spring Trout (Alabalık–Kaynak), Large-spotted/Mountain Trout (Alabalık–Büyük Benekli–Dağ Alabalığı), and Sturgeon–Common Two-banded (Mersin–Sivriburun) (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

In Turkey, facilities with concrete ponds are located in the provinces of Adana, Adıyaman, Afyonkarahisar, Amasya, Antalya (mainly), Artvin (mainly), Aydın, Balıkesir, Bilecik, Bitlis, Bolu (mainly), Burdur, Bursa, Çanakkale, Çankırı, Çorum, Denizli (mainly), Diyarbakır, Elazığ, Erzincan, Eskişehir, Giresun (mainly), Gümüşhane, Hakkari, Hatay, Isparta, Mersin (mainly), İzmir, Kars, Kastamonu, Kayseri, Kırklareli, Kocaeli, Konya, Kütahya, Malatya, Manisa, Kahramanmaraş, Mardin, Muğla (mainly), Muş, Niğde, Ordu (mainly), Rize, Sakarya, Samsun, Siirt, Sinop, Sivas, Tokat, Trabzon (mainly), Tunceli, Şanlıurfa, Uşak, Van, Yozgat, Bayburt, Karaman, Şırnak, Bartın, Ardahan, Iğdır, Yalova, Karabük, Osmaniye, and Düzce (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

1.2.3.5. Earthen Pond

Earthen ponds are pond environments prepared by excavating the soil to suitable dimensions and filling the excavated area with surface or groundwater (Tezel, 2015). Certain soil criteria must be met for the construction of earthen ponds. For example, it is stated that the soil structure of the land should have at least a 1-meter-deep clayey and calcareous profile (Atamanalp & Kocaman, 2007). One of the main advantages of earthen ponds is that their construction cost is lower compared to concrete ponds (Arslan & Yağanoğlu, 2020). Another advantage of using earthen ponds in aquaculture is the transformation of soil types that are unsuitable for agricultural production into ponds suitable for fish farming. In this way, a source of income is provided to the local population (Mutlu & Atar, 2011). It has been reported that in Milas district of Muğla, due to high soil salinity and unsuitability for agricultural activity, there is a common tendency to excavate and convert land into earthen ponds (Tezel, 2015).

In a survey conducted with employees working in earthen pond enterprises, information was obtained about the problems occurring during earthen pond aquaculture processes (Tezel & Güllü, 2017). It is stated that the biggest problem experienced in earthen ponds is the accumulation of organic waste at the pond bottom. The structure of the pond bottom and soil slippages occurring at the pond bottom, which affect the hydrodynamic structure of the pond, are reported as the main reasons for the accumulation of organic matter at the pond bottom (Tezel & Güllü, 2017). Since the accumulation of organic matter increases the oxygen demand of the pond, it should be cleaned frequently (Tezel, 2015).

In Turkey’s earthen pond systems, species produced include Rainbow Trout, Carp (Mirror and Scaled), Aquarium Fish, Frog, Medicinal Leech, Sandworm (Logworm), Shabut, Karabalık–Dwarf Catfish, European Seabass, Artemia, Gilthead Seabream, Goldblotch Grouper (Sarıağız–Granyöz), Dentex (Sinagrit), Red Seabream (Mercan–Fangri), Antennae Coral–Blue Spotted Grouper (Mercan–Antenli–Mavi Benekli), Dusky Grouper (Lahoz–Grida), Meagre (Minekop–Kötek), Brown Meagre (Eşkina–Mavruşgil), Turbot, Sole, Sturgeon–Cod (Mersin–Morina), Mullet (Kefal–Has), Red-banded Seabream (Mercan–Kırmızı Bantlı), Meagre (Trança), Red Seabream (Mercan–Kırma), Dentex (Sinagrit), Blue Crab, Common Two-banded Seabream (Sivriburun Karagöz), Whiteleg Shrimp, Amberjack (Sarıkuyruk–Avcı), Sole, Senegal Sole (Dil–Senegal), Meagre (Trança), Red Mullet (Barbun), Nile Tilapia (Tilapya–Nil), Medicinal Leech, and Catfish (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

In Turkey, aquaculture facilities with earthen ponds are located in the provinces of Ankara, Antalya, Aydın, Balıkesir, Bolu, Burdur, Çanakkale, Çorum, Edirne, Elazığ, Erzurum, Eskişehir, Hatay, Isparta, Mersin, İzmir, Kayseri, Malatya, Manisa, Kahramanmaraş, Muğla (mainly), Niğde, Sakarya, Samsun, Uşak, Van, and Yozgat (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

1.2.3.6.Tank

This is a production system carried out in circular and rectangular tank structures, built using various materials and located either indoors or outdoors. These systems also include biological treatment units (Bernal-Higuita et al., 2023).

In Turkey’s facilities with tank systems, species produced include Rainbow Trout, Gilthead Seabream, Striped Seabream (Mırmır), Meagre (Minekop–Kötek), European Seabass, Red Seabream (Mercan–Fangri), Dentex (Sinagrit), Dusky Grouper (Lahoz–Grida), Goldblotch Grouper (Sarıağız–Granyöz), Common Two-banded Seabream (Sivriburun Karagöz), Amberjack (Sarıkuyruk–Avcı), Medicinal Leech, Aquarium Fish, Spirulina, Goldblotch Grouper (Sarıağız–Granyöz), Dentex (Sinagrit), Red Seabream (Mercan–Kırma), Antennae Coral–Blue Spotted Grouper (Mercan–Antenli–Mavi Benekli), Clownfish (Palyaço), Meagre (Trança), Brown Meagre (Eşkina–Mavruşgil), Ark Clam (Kidonia), Oyster (İstiridye), Surf Clam (Akivades), and Sole (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

In Turkey, facilities with tank systems are located in the provinces of Adana, Aydın, Çanakkale, Erzurum, Gaziantep, Isparta, Mersin, İzmir, Kayseri, Muğla, and Muş (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025). In intensive culture systems, due to the aeration equipment used inside the tanks, energy consumption and related environmental impacts arise (Bernal-Higuita et al., 2023).

1.2.3.7.Park

The park system of aquaculture is prepared by enclosing an area with fences approximately 80 cm high and covering it with netting (Serdar, 2021). In Turkey, species produced in parks include Black Snail, Sand Clam (Tellina), and Surf Clam (Akivades) (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025). Aquaculture in parks is carried out in Balıkesir, Bursa, and İzmir provinces (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2025).

1.2.4. Classification According to Whether It Is Integrated or Not

In addition to being implemented as traditional systems where only fish are raised, aquaculture systems can also be established as integrated systems such as Rice–Fish, Duck–Fish, Chicken–Fish, and Aquaponic Systems, where fish are raised together with different animals and plants.

Integrated systems include the Rice–Fish System, Duck–Fish System, Chicken–Fish System, and Aquaponic System. The cultivation of different organisms in integrated systems is carried out to ensure that by-products produced by one organism in the integrated system can be used as beneficial inputs by another species (Ahmad et al., 2021).

1.2.4.1.1.Pirinç-Balık Sistemi

Rice–fish systems are among the production systems that ensure sustainable water management. In this system, fish are raised simultaneously or alternately in the water areas where rice is cultivated (Ruddle, 1982). It is believed that the rice–fish system began 6,000 years ago in Southeast Asia when irrigation waters from rivers brought fish into rice fields, and over time it developed into a culture system where both plants and animals are raised together (Yifan et al., 2023; Ruddle, 1982). Among the South Asian countries producing with the integrated rice–fish culture system, China stands out. According to research data, rice–fish farming is widely practiced in China’s Heilongjiang, Shanxi, Ningxia, Henan, Jiangsu, Anhui, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Hunan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Fujian, Guangxi, Guangdong, Jilin, and Sichuan regions (Yifan et al., 2023). In integrated rice–fish farming, since fish are more affected by environmental temperature conditions than rice, temperature is a parameter that must be carefully managed for the productivity of the culture (Yifan et al., 2023).

This system is both economically and ecologically beneficial. In this system, the fish cultured in the field protect the rice by eating harmful insects in the water, thus eliminating the need for chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Furthermore, the manure left by the fish swimming among the rice plants enhances the productivity of the rice seedlings. Figure 5 shows a schematic representation of integrated rice–fish farming.

1.2.4.1.2. Duck–Fish System

The Duck–Fish System is a polyculture system in which fish and ducks are raised together in the same pond. This system offers many advantages for farmers. These advantages can be listed as follows (FAO, 2025b):

- Duck droppings fertilize the pond, and pond fertilization reduces the use of fish feed.

- The movement of ducks in the pond loosens the pond bottom and allows nutrients from the soil to enter the pond, thus increasing productivity.

- The swimming of ducks in the pond aerates the pond.

- In these systems, duck houses are built on pond dikes; therefore, no additional land is needed for duck rearing.

- In this system, ducks meet their feed requirements from aquatic plants, insects, larvae, and worms on the pond, reducing the need for supplementary feed.

An example of integrated duck–fish farming is shown in Figure 6.

1.2.4.1.3. Chicken–Fish System

Poultry farming can be integrated with fish culture to provide benefits such as reducing fertilizer and feed costs in fish production. In these systems, placing chickens above or near the pond allows chicken droppings to reach the pond and increase productivity (FAO, 2025c). In this system, waste from chicken coops placed above or near the fish pond reaches the pond and is used as natural fertilizer for the pond. The natural fertilizer provided contributes to the growth of aquatic plants, algae, and other organisms that serve as food sources for the fish. Fish waste, in turn, provides the nutrients needed by the vegetation around the pond. Figure 7 shows the integrated chicken–fish farming system.

1.2.4.1.4.Akuaponik Sistem

Aquaponics is an innovative and sustainable food production technology that combines aquaculture (fish farming) and hydroponics (soilless plant cultivation) (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). The system is based on the symbiotic relationship between fish and plants. Nutrients in the waste produced by fish naturally fertilize the plants, and the plants, in turn, use these nutrients and act as a filter that cleans the water for the fish (Meyer et al., 2025). The filtered water then returns to the fish tank, contributing to a healthy environment for the fish.

Aquaponic systems offer environmental and economic benefits such as reusing water, enabling aquaculture in areas with water scarcity, reducing the need for chemical fertilizers that may be harmful to consumers’ health, and improving productivity in both fish and plant production (Meyer et al., 2025). This method is an environmentally friendly approach in terms of sustainable agriculture and water management..

Aquaponic systems can be applied at different scales depending on preference and purpose. There are systems at various scales, including household hobby systems, commercial-scale systems, and educational systems. Types of aquaponic systems include raft systems, media-filled grow beds, nutrient film technique (NFT), wick systems, and drip systems (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). The types of aquaponic systems also vary according to the type of growing bed used. Types of aquaponic systems include raft systems, media-filled grow beds, nutrient film technique (NFT), wick systems, and drip systems (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018).

In aquaponic systems, nutrients in wastewater are recovered by being absorbed by plants. Microorganisms are also necessary to transform fish-derived waste. In aquaponic systems, bacteria carry out the nitrogen cycle. To convert nitrogen into a form usable by plants, ammonia is converted to nitrite by nitrifying bacteria, and nitrite is converted to nitrate. Because dissolved substances are filtered by plants in aquaponic systems, the system’s need for biological and mechanical filtration is reduced (Yavuzcan Yıldız & Pulatsü, 2022). Figure 8 shows the components of an aquaponic system.

Because the water cycle in aquaponic systems is maintained in a closed loop, water consumption remains at a minimum. Designed to achieve the maximum yield with minimal water use, aquaponic systems are highly advantageous in terms of resource conservation in areas experiencing water scarcity (Türker, 2018). Aquaponic systems make sustainable agriculture possible especially in cities or small spaces and provide high productivity in limited areas (Meyer et al., 2025).

Since the nutrients in fish waste provide natural fertilizer for plants, there is no need for chemical fertilizers, thereby reducing the risk of environmental harm (Meyer et al., 2025). Aquaponic systems are highly environmentally friendly due to their water reuse and the absence of chemical fertilizer requirements. In particular, the environmental burdens caused by the production of nitrogen fertilizers such as fossil fuel depletion, global warming, and acidification, can be eliminated through the use of this system (Chen et al., 2020).

Traditional aquaculture systems, unlike integrated systems, can be defined as the cultivation of a single species or multiple species of aquatic organisms. Traditional systems allow the farming of fish, mussels, shrimp, and other shellfish species, as well as various aquatic plants, in inland waters such as lakes and rivers, and in structures such as ponds, tanks, canals, and cage systems. Although water quality parameters such as oxygen, temperature, pH, and salinity vary depending on the species being cultured, they are of critical importance.

Ahmad, A., Abdullah, S., Hasan, H. A., Othman, A., & Ismail, N. (2021). Aquaculture industry: Supply and demand, best practices, effluent and its current issues and treatment technology. Journal of Environmental Management, 112271.

Ahmed, N., & Thompson, S. (2019). The blue dimensions of aquaculture: A global synthesis. Science of the Total Environment, 851–861.

Anyanwu, P., Gabriel, U., Akinrotimi, O., Bekibele, D., & Onunkwo, D. (2007). Brackish water aquaculture: a veritable tool for the empowerment OF Niger Delta communities. Scientific Research and Essay, 295-301.

Arslan, G., & Yağanoğlu, E. (2020). TOPRAK VE BETON HAVUZLARDA YAPILAN ALABALIK YETİŞTİRİCİLİĞİNİN SU VE TOPRAKTAKİ BAZI FİZİKO-KİMYASAL PARAMETRELERE ETKİSİ. Menba Kastamonu Üniversitesi Su Ürünleri Fakültesi Dergisi, 1-5.

Atamanalp, M., & Kocaman, E. M. (2007). FARKLI TİP HAVUZLARIN YAVRU ALABALIK YETİŞTİRİCİLİĞİNDE KARLILIK ÜZERİNE ETKİSİNİN EKONOMİK ANALİZİ. Anadolu Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi, 1-4.

Atay, D. (1986). Balık Üretim Tesisleri ve Planlaması. Ankara: Ankara Üniv. Ziraat Fak. Yayınları.

Bernal-Higuita, F., Acosta-Coll, M., Ballester-Merelo, F., & De-la-Hoz-Franco, E. (2023). Implementation of information and communication technologies to increase sustainable productivity in freshwater finfish aquaculture – A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137124.

Boyd, C. (2009). Aquaculture, Freshwater. C. Boyd, & G. Likens (Dü.) içinde, Encyclopedia of Inland Waters (s. 234-241). Academic Press.

Bregnballe, J. (2015). A Guide to Recirculation Aquaculture. the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and EUROFISH International Organization.

Carmo, F., Amboni, R., Figueiredo, J., Owatari, M., & Bellettini, F. (2025). Physicochemical characterization and sensory acceptability of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fillets farmed in fresh or brackish water. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 107095.

Chen, P., Zhu, G., Kim, H.-J., Brown, P., & Huang, J.-Y. (2020). Comparative life cycle assessment of aquaponics and hydroponics in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Cleaner Production, 122888.

Çelik, M. (2006). SAL SİSTEMİNDE, MİDYENİN (Mytilus galloprovincialis, LAMARK, 1819 )TOPLANMASININ VE BÜYÜTÜLMESİNİN ARAŞTIRILMASI. ONDOKUZ MAYIS ÜNİVERSİTESİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ.

Dikel, S. (2005). KAFES BALIKÇILIĞI. Adana: ÇUKUROVA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SU ÜRÜNLERİ FAKÜLTESİ YAYINLARI.

El-Sayed, A.-F. M. (2019). Tilapia culture. Academic Press.

FAO. (2025a, 01 26). 4. AQUACULTURE METHODS AND PRACTICES: A SELECTED REVIEW. www.fao.org: https://www.fao.org/4/t8598e/t8598e05.htm

FAO. (2025b, February 2). FAO.org. Animal-Fish Systems: https://www.fao.org/4/y1187e/y1187e14.htm

FAO. (2025c, February 02). Integrated chicken-fish farming. FAO.org: https://www.fao.org/4/y1187e/y1187e15.htm

Kargın, H., & Bilgüven, M. (2018). Akuakültürde Akuaponik Sistemler ve Önemi. BURSA ULUDAĞ ÜNİVERSİTESİ ZİRAAT FAKÜLTESİ DERGİSİ, 159-173.

Laird, L. (2001). Mariculture Overview. Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Second Edition) (s. 1572-1577). Academic Press.

Li, D., & Liu, S. (2019). Chapter 4 – Water Quality Evaluation. Water Quality Monitoring and Management (s. 113-159). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811330-1.00004-1

Meyer, J., Weisstein, F., Kershaw, J., & Neves, K. (2025). A multi-method approach to assessing consumer acceptance of sustainable aquaponics. Aquaculture, 741764.

Mutlu, M. A., & Atar, H. H. (2011). Toprak Havuzlarda Su Ürünleri Yetiştiriciliği. Ziraat Mühendisliği, 30-33.

Ngo, H.,Guo, W.,Tram, Vo T.,Nghiem, L.,Hai, F., 2017, Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Biological Treatment of Industrial Effluents,35-77

Ruddle, K. (1982). Traditional integrated farming systems and rural development: the example of ricefield fisheries in Southeast Asia. Agricultural Administration, 1–11.

Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. (2025). Su ürünleri yetiştiriciliği. https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/Konular/Su-Urunleri/Su-Urunleri-Yetistiriciligi

Sedgwick, S. D., 1978. Trout Farming Handbook. Schdium International Inc., New York.

Serdar, S. (2021). AKİVADES BİYOLOJİSİ VE YETİŞTİRİCİLİĞİ. ÇİFT KABUKLU YETİŞTİRİCİLİĞİNDE TEMEL KONULAR (s. 89-122). İksad Yayınevi.

Tezel, R. (2015). Milas Bölgesindeki Toprak Havuz İşletmelerinin Mevcut Durum Analizinin Yapılması ve Sürdürülebilirlikleri İçin Çözüm Önerileri Geliştirilmesi. Yüksek Lisans Tezi. Muğla.

Tezel, R., & Güllü , K. (2017). TOPRAK HAVUZLARDA DENİZ BALIKLARI ÜRETİMİ YAPAN İŞLETMELERİN SÜRDÜRÜLEBİLİRLİKLERİNİNSAĞLANMASI ÜZERİNE BİR ARAŞTIRMA SAĞLANMASI ÜZERİNE BİR ARAŞTIRMA. Journal of Aquacultre Enginnering and Fisheries Research , 128-140.

TURKSTAT (Turkish Statistical Institute). (2024, Aralık 29). Fishery Products, 2023. TURKSTAT : https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Su-Urunleri-2023-53702&dil=2

Türker, H. (2018). Akuaponik Yetiştiricilik Sisteminde Farklı Bitkilerin Besin Dinamiği. Aquatic Sciences and Engineering, 77-83.

Uğural, B., SEREZLİ, R., HAMZAÇEBİ, S., ÖZTÜRK, F., & GÜNDÜZ, H. (2018). ULUSLARARASI SU VE ÇEVRE KONGRESİ KAPALI DEVRE YETİŞTİRİCİLİK SİSTEMLERİ GEREKLİ MİDİR? B. Uğural, R. SEREZLİ, S. HAMZAÇEBİ, F. ÖZTÜRK, & H. GÜNDÜZ içinde, Kapalı Devre Yetiştiricilik Sistemleri Gerekli Midir?

Ustaoğlu Tırıl, S., & Dalkıran, G. (2005). Akuakültürde Kapalı Devre Sistemlerinin Kullanımı, Türk Sucul Yaşam Dergisi, 454-460.

Yavuzcan Yıldız, H., & Pulatsü, S. (2022). Sıfır atığa doğru: Su ürünleri yetiştiriciliğinde sürdürülebilir atık yönetimi. Su Ürünleri Dergisi, 341-348.

Yifan, L., Tiaoyan, W., Shaodong, W., Xucan, K., Zhaoman, Z., Hongyan, L., & Jiaolong, L. (2023). Developing integrated rice-animal farming based on climate and farmers choices. Agricultural Systems, 103554.