Module 7: Carbon Footprint and Waste Generation in Aquaculture

Summary / Description Text

This module provides a detailed discussion of the concept of carbon footprint and waste management in aquaculture production. The carbon footprint is defined as the total greenhouse gas emissions released throughout the entire life cycle of a product (raw material extraction, production, distribution, consumption and disposal stages). The calculation process is based on the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology, guided by standards such as ISO 14067, PAS 2050 and the GHG Protocol.

The module emphasizes that feed production and energy consumption are the main contributors to the carbon footprint of aquaculture activities. It presents comparisons of the carbon footprint of different production systems (pond, cage, recirculation/RAS), highlighting the critical importance of renewable energy use for sustainability.

In the second part of the module, the solid wastes generated in aquaculture facilities (uneaten feed, feces, net and equipment waste, construction waste, etc.) are examined, along with their environmental impacts (oxygen depletion, nitrogen load, pollution) and management strategies.

Keywords: carbon footprint, life cycle assessment (LCA), PAS 2050, ISO 14067, greenhouse gas emissions, feed production, energy consumption, recirculating systems, waste management, solid waste.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module, participants will be able to:

• Define the concept of carbon footprint and explain the calculation process based on the LCA methodology.

• Interpret the role of international standards such as ISO 14067, PAS 2050 and the GHG Protocol in carbon footprint calculations.

• Analyze the impacts of feed and energy use on the carbon footprint of aquaculture production.

• Compare the carbon footprint performance of different aquaculture production systems (pond, cage, RAS).

• Identify the types of solid waste generated in aquaculture facilities and their environmental impacts.

• Discuss sustainable strategies for waste management and carbon reduction.

Presentation File

1.8. Carbon Footprint in Aquaculture Production

The product carbon footprint is the calculation of the amount of greenhouse gas emissions released at all stages of a product’s life cycle, including design, raw material acquisition, production, distribution, use, and waste management after it reaches its end-of-life stage (International Organization for Standardization [ISO], 2018). Another definition of the carbon footprint in the literature describes it as “a specific measure of the total carbon dioxide emissions caused directly and indirectly by an activity or accumulated over the life stages of a product” (Wiedmann & Minx, 2008). Carbon footprint assessment quantitatively evaluates the environmental impacts of a product in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. The methodologies used in product carbon footprint calculations are fundamentally based on the life cycle assessment approach but are framed by different standards and guidelines. Standards such as ISO 14067, PAS 2050, and the GHG Protocol – Product Standard standardize the calculation of greenhouse gas emissions occurring throughout the life cycle of a product (ISO, 2018; British Standards Institution [BSI], 2011; World Resources Institute & World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2011).

The life cycle assessment (LCA) approach is a methodology framed by ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards to identify the environmental impacts of a product at all stages from raw material acquisition to disposal (ISO, 2006a; ISO, 2006b). In LCA, the analysis is carried out in four main phases for the product whose environmental impacts are to be assessed: goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation (ISO, 2006a). The ISO 14067:2018 – Greenhouse gases — Carbon footprint of products standard is based on the LCA approach in carbon footprint calculations and defines system boundaries as in ISO 14040/44 (ISO, 2018). ISO 14067:2018 is a standard prepared as a guideline for how to account for greenhouse gas emissions and removals in product carbon footprint calculations (ISO, 2018). This standard particularly clarifies the boundaries for the carbon footprint of products. In summary, the carbon footprint is calculated based on the life cycle assessment (LCA) methodology and typically uses the Global Warming Potential (GWP100) factors published by the IPCC (ISO, 2006b; ISO, 2018; IPCC, 2013).

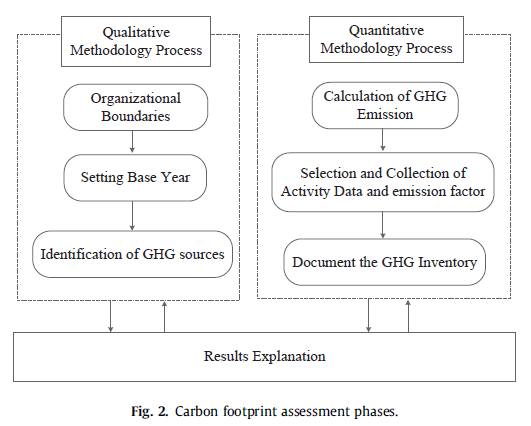

The carbon footprint assessment process consists of two main stages encompassing qualitative and quantitative methodologies. In the qualitative methodology stage, organizational boundaries are first defined, then the base year is determined, and greenhouse gas sources are identified. In the quantitative methodology stage, greenhouse gas emissions are calculated, necessary activity data and emission factors are collected, and the resulting outcomes are documented as a greenhouse gas inventory. In the final stage, the outputs of both methodologies are combined to ensure the disclosure of the results. Figure 1 summarizes the stages of carbon footprint assessment (Chang et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Stages of carbon footprint assessment (Chang et al., 2017).

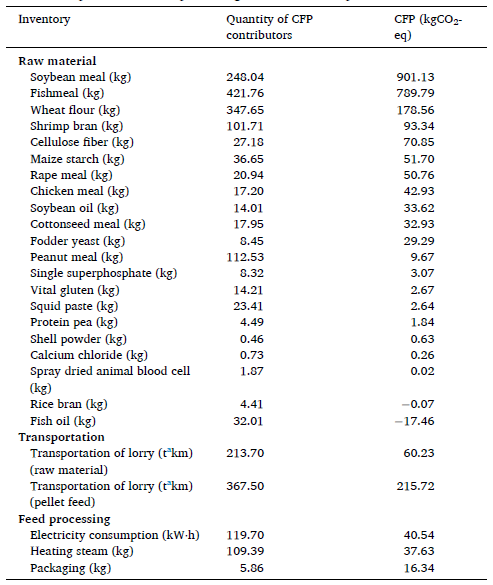

When examining the carbon footprint resulting from aquaculture activities, raw materials such as feed and electricity are taken into account. In this context, the carbon footprint arising from feed usage, in particular, plays a significant role in aquaculture operations. In the calculation of the carbon footprint from feed production, the focus is on the production and processing of the feed to be used, as well as the transportation of feed ingredients and the manufactured feed itself. In a study conducted by Rong et al. (2025), the carbon footprint of the raw material, processing, and transportation stages of feed used for the production of one ton of shrimp was calculated (Rong et al., 2025). Because soybean meal, fish meal, and wheat flour are frequently used as feed ingredients in aquaculture, the carbon footprint from these materials is dominant. Table 1 summarizes the carbon footprint of feed production used in the production of one ton of shrimp.

Table 1. Carbon footprint of feed production required for one ton of shrimp production (Rong et al., 2025).

Energy consumption in aquaculture includes the electricity required to operate the equipment used during the aquaculture process and the fossil fuels consumed during the transportation stage of the produced products (Rong et al., 2025). Another focus considered in the calculation of the carbon footprint in aquaculture activities is biological carbon (Rong et al., 2025). Biological carbon accounts for the CO₂ released as a result of the respiration of the aquatic products produced in aquaculture.

1.8.1. Steps for Calculating the Carbon Footprint in Aquaculture

According to the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology, the carbon footprint calculation is carried out in four main stages. First, the goal and scope must be defined (ISO, 2006b). At this point, it is necessary to determine the system boundaries and the functional unit for the product and/or process for which the carbon footprint will be calculated. When calculating the carbon footprint in aquaculture, the assessment is performed through processes such as the setup of the aquaculture system, aquaculture activities, and waste management (Chang et al., 2017; Rong et al., 2025; Sun et al., 2023). The scope of these assessments varies depending on the choice of system boundaries to be considered. Different system boundaries such as cradle-to-grave, cradle-to-gate, and gate-to-gate define the focus and scope of the calculation.

In the carbon footprint analysis of aquaculture production systems, the functional unit is important for determining the greenhouse gas emissions released, expressed as carbon dioxide equivalent, for the production of a specific quantity of aquatic products. For example, in some studies where the carbon footprint was calculated using the LCA methodology, the functional units were defined as 1 kilogram of aquatic product per carbon dioxide equivalent and 1 ton of aquatic product per carbon dioxide equivalent (Chang et al., 2017; Rong et al., 2025; Sun et al., 2023).

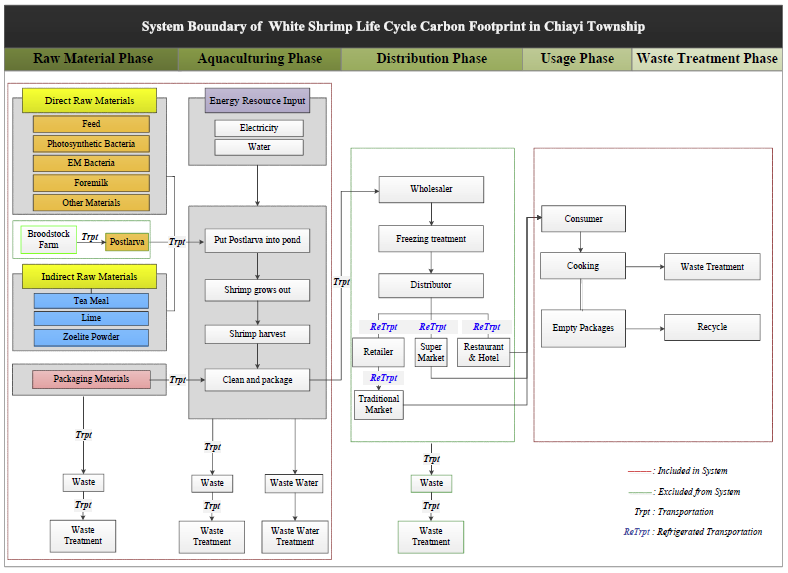

In accordance with the LCA methodology, the life cycle stages and processes of the production for which the system boundaries are defined must be clearly specified in product carbon footprint calculations. For example, in a study where the system boundary was defined as cradle-to-grave, the greenhouse gas emissions generated at five stages — raw material acquisition, aquaculture, distribution, consumption, and waste management — for the production of 1 kilogram of white shrimp were determined in terms of carbon dioxide equivalent (Chang et al., 2017). Figure 2 presents in detail all the stages examined within the scope of a study where the system boundary was defined as cradle-to-gate (Chang et al., 2017).

Figure 2. System boundary of the carbon footprint of white shrimp (Chang et al., 2017).

Figure 2. System boundary of the carbon footprint of white shrimp (Chang et al., 2017).

In the study conducted by Chang et al. (2017), the carbon footprint resulting from the production of 1 kilogram of shrimp in a pond system was calculated (Chang et al., 2017). Within this calculation, the aeration systems used for pond aeration were considered the primary source of electricity consumption, while the amount of water used to fill the ponds represented the raw material stage within the system boundaries. In the aquaculture stage of the study, various types of feed (traditional feeds and biological feeds) used for feeding the shrimp and the chemicals used to maintain the health of the aquaculture environment were taken into account. In the distribution stage included in the study, the carbon emissions from the fuel (diesel) used and from refrigeration were calculated. For the consumption stage of the study, the water and natural gas used for cooking 1 kilogram of shrimp were considered. The final stage calculated in the study was the waste management stage. Under waste management activities, the carbon emissions resulting from the incineration of wastes generated during shrimp processing, the recycling of packaging waste, and the treatment of dirty wastewater collected from ponds were all accounted for.

In another study where the system boundaries were defined as cradle-to-gate (Rong et al., 2025), the carbon footprint for the production of 1 ton of shrimp was calculated for two stages: the installation of the aquaculture system and the production stage (Rong et al., 2025). Within the scope of the study, the carbon emissions were calculated for the production of the materials used in the construction of the pond system, the transportation of these materials to the installation site, land use, the use of feed, electricity, and water in aquaculture activities, and the emissions arising from the respiration of the shrimp (Rong et al., 2025). The system boundaries of the activities included in the calculation are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. System boundary for carbon footprint assessment in shrimp farming (Rong et al., 2025).

Figure 3. System boundary for carbon footprint assessment in shrimp farming (Rong et al., 2025).

In accordance with the LCA methodology, the third step in product carbon footprint calculation is the life cycle impact assessment (ISO, 2006b). In this context, emission factors are obtained from various databases and used in the calculations. It is observed that studies calculating the carbon footprint for aquaculture frequently utilize the Ecoinvent database (Rong et al., 2025; Sun et al., 2023). During the life cycle impact assessment stage, greenhouse gas emissions derived from the inventory are classified under the global warming category and converted into carbon dioxide equivalents (CO₂-eq) using the Global Warming Potential (GWP) factors published by the IPCC. This conversion allows the contributions of different greenhouse gases to climate change to be expressed on a common scale, after which all values are aggregated to calculate the system’s total carbon footprint (ISO, 2018; IPCC, 2021). It has been reported that in the analysis and calculation of the collected activity data, most aquaculture carbon footprint studies have applied the PAS 2050 method (Chang et al., 2017).

According to the PAS 2050 method, a carbon footprint study begins with the identification of the functional unit and process boundaries; then a process flow diagram is prepared, the boundaries are reviewed with a focus on priority flows, data are collected and calculations are performed using emission factors, and finally, the reliability of the results is verified through uncertainty analysis (BSI, 2011; WKC Group, 2023). According to the PAS 2050 method, the equation for calculating greenhouse gas emissions in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents is as follows:

CEa = Greenhouse gas emissions for material A (kg CO₂e)

ADa = Activity data amount of material A (unit)

EFa = Emission factor of material A (kg CO₂e/unit)

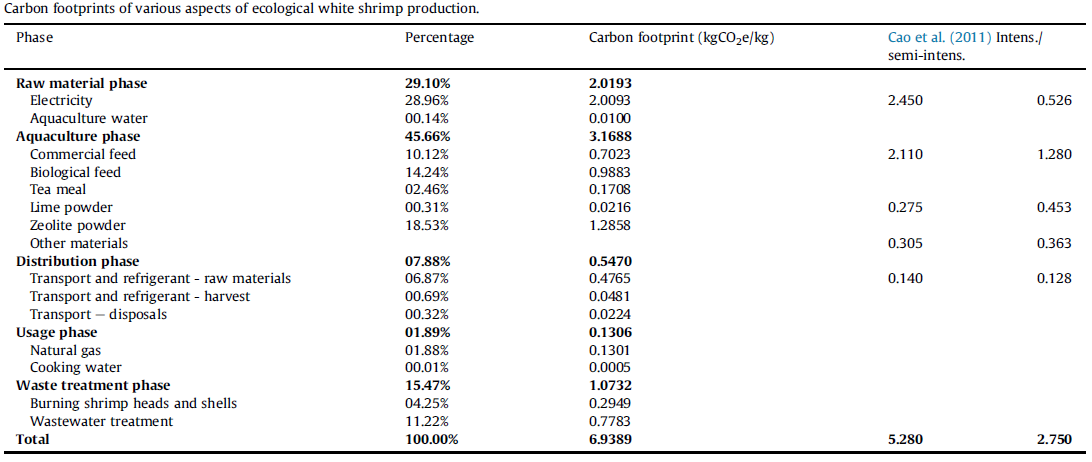

In accordance with the LCA methodology, the final step in product carbon footprint calculation is life cycle interpretation (ISO, 2006b). This stage aims to assess the reliability of the results, evaluate uncertainties, and identify opportunities for improvement (ISO, 2006). Through life cycle interpretation, processes such as feed production, energy consumption, water use, and waste management in aquaculture can be comparatively analyzed in terms of their contribution to the carbon footprint. In this way, priority areas for emission reduction are identified and strategic decisions are developed to mitigate environmental impacts. The main sources contributing to the carbon footprint in aquaculture activities are electricity consumption and feed production (Rong et al., 2025; Chang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2024). The carbon footprint results of the study, in which the system boundary was defined as cradle-to-grave and the functional unit as 1 kilogram of shrimp, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Carbon footprint results for the production of 1 kilogram of shrimp (Chang et al., 2017).

Table 2. Carbon footprint results for the production of 1 kilogram of shrimp (Chang et al., 2017).

When examining the information in Table 2, the highest carbon footprint occurred in the aquaculture phase (3.1688 kg CO₂e/kg), with feed consumption making a significant contribution to this share. In the raw material phase (2.0193 kg CO₂e/kg), electricity consumption was influential. In aquaculture, electricity is used to bring water to the desired temperature range, in feed preparation, and for aeration equipment (Chang et al., 2017; Rong et al., 2025). In recirculating aquaculture systems, energy consumption varies between 2.9 and 81.48 kWh/kg depending on factors such as location and production intensity (Badiola et al., 2018). Rong et al. (2025) reported in their study that the carbon emissions from electricity consumption in pond-based shrimp production accounted for more than 50% of the total carbon footprint (Rong et al., 2025).

1.8.2. Comparison of the Carbon Footprint of Aquaculture Systems

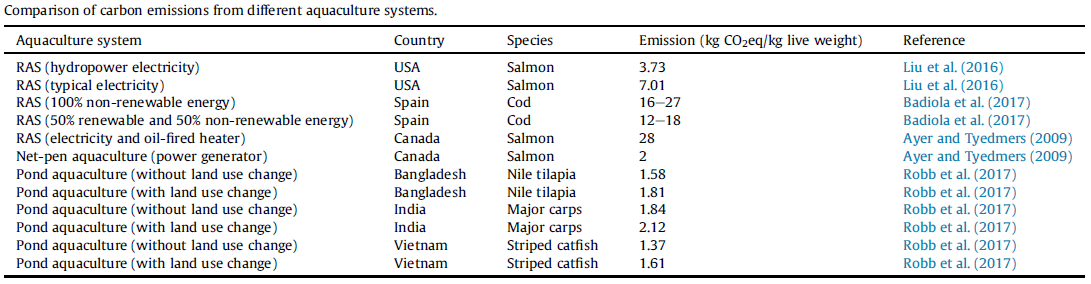

Because systems in the aquaculture sector differ in terms of raw materials consumed, the carbon footprint generated by aquaculture production systems varies considerably. Due to this variation, identifying the most environmentally sustainable system can only be achieved through a comprehensive examination and comparison of all systems. For example, in a study comparing the carbon footprint of salmon produced in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS)—which have high energy consumption due to various wastewater treatment equipment—with that of salmon produced in cage systems, it was found that the carbon footprint of salmon produced in RAS (7.01 t CO₂eq/t) was twice as high as that in cage systems (3.39 t CO₂eq/t) (Liu et al., 2016). The higher carbon footprint of salmon produced in RAS is attributed to the high electricity consumption in the system and the fossil fuel-based nature of the electricity used.

Electricity consumption, which is the primary carbon footprint factor in aquaculture, can be reduced by prioritizing the use of renewable energy sources for system operations. In RAS, where water consumption is significantly lower but electricity consumption is much higher compared to other systems, obtaining energy from environmentally friendly sources is of critical importance to ensure sustainability-focused production. The results obtained from carbon footprint studies conducted for different aquaculture systems are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Carbon emission comparison for aquaculture systems (Ahmed & Turchini, 2021).

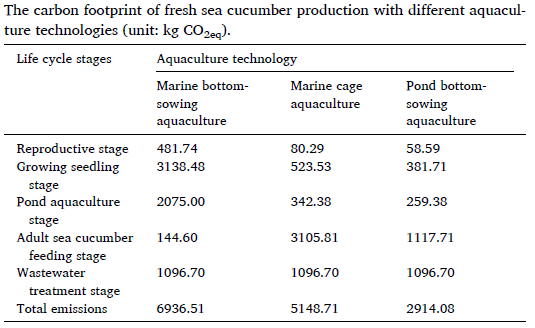

When examining the information in Table 3, it is observed that the highest carbon footprint occurs in RAS aquaculture operated with 100% non-renewable energy sources (16–27 kg CO₂e/kg), while the lowest carbon footprint is found in pond aquaculture where no land-use change effects are present (1.37 kg CO₂e/kg). Another study focusing on system-level comparisons of carbon footprints in aquaculture production was conducted by Yang et al. (2024) (Yang et al., 2024). In this study by Yang et al. (2024), the carbon footprint of sea cucumber production using different aquaculture techniques was compared. The functional unit was defined as 1 kilogram of sea cucumber, and the system boundaries were set as cradle-to-gate. The results obtained are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Carbon footprint of fresh sea cucumber production using different aquaculture technologies (unit: kg CO₂eq) (Yang et al., 2024).

When examining the results of the study comparing different aquaculture systems across various life cycle stages, it is observed that emissions from production and wastewater treatment are dominant. The highest carbon footprint was recorded in seabed ranching aquaculture (Yang et al., 2024).

1.9. Wastes Generated in Aquaculture Production and Their Management

During the construction and operation of aquaculture facilities, solid wastes are generated and must be effectively managed. The solid wastes produced during the construction of aquaculture facilities are classified into three groups: excavation wastes, non-hazardous construction wastes, and hazardous wastes (e.g., waste oils, hydraulic fluids, oil filters, contaminated cleaning materials) (Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı-Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, 2017).

Depending on the aquaculture system, various solid wastes are generated during facility operation. For example, in cage aquaculture systems, wastes such as netting from cages and plastic ropes are produced (Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı-Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, 2017). In all aquaculture facilities, feeds used for the nutrition of cultured species are a major source of solid waste. Feed contributes to solid waste generation either in the form of feces produced through the organism’s metabolism or as uneaten feed. According to the literature, even in high-efficiency facilities, about 30% of the feed used in aquaculture turns into solid waste (Miller & Semmens, 2002; Dauda et al., 2019). The solid wastes generated are divided into suspended solids and settleable solids. The decomposition of these solids increases the COD and BOD parameters in the water, which in turn lowers the dissolved oxygen levels. Moreover, nitrogen released as a result of biological degradation is a factor that affects the health of cultured organisms; therefore, nitrogen removal is highly important in aquaculture facilities.

Reference

Ahmed, N., & Turchini, G. M. (2021). Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS): Environmental solution and climate change adaptation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 297, 126604. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2021.126604

Ayer, N.W., Tyedmers, P.H., 2009. Assessing alternative aquaculture technologies: life cycle assessment of salmonid culture systems in Canada. J. Clean. Prod. 17, 362-373.

Badiola, M., Basurko, O.C., Gavi~na, G., Mendiola, D., 2017. Integration of energy audits in the life cycle assessment methodology to improve the environmental performance assessment of recirculating aquaculture systems. J. Clean. Prod. 157, 155-166.

Badiola, M., Basurko, O. C., Piedrahita, R., Hundley, P., & Mendiola, D. (2018). Energy use in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS): A review. Aquacultural Engineering, 81, 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AQUAENG.2018.03.003

British Standards Institution (BSI). (2011). Guide to PAS 2050:2011—How to carbon footprint your products, identify hotspots and reduce emissions in your supply chain. BSI. https://www.co2-sachverstaendiger.de/pdf/BSI%20Guide%20to%20PAS2050.pdf

Cao, L., Diana, J.S., Keoleian, G.A., Lai, Q.M., 2011. Life cycle assessment of Chinese shrimp farming systems targeted for export and domestic sales. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (15), 6531-6538.

Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı-Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. (2017). Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığının Çevresel Etki Değerlendirme (ÇED) alanında kapasitesinin güçlendirilmesi için teknik yardım projesi: Kitapçık B33 – Su ürünleri işleme ve yetiştirme tesislerinin çevresel etkileri. NIRAS IC Konsorsiyumu.

Chang, C.-C., Chang, K.-C., Lin, W.-C., & Wu, M.-H. (2017). Carbon footprint analysis in the aquaculture industry: Assessment of an ecological shrimp farm. Journal of Cleaner Production,168,1101-1107.

Daudaa, A.B., Ajadib, A., Tola-Fabunmic, A. S., Akinwoled, A.O. (2019). Waste production in aquaculture: Sources, components and managements in different culture systems, Aquaculture and Fisheries 4, 81–88.

Liu, Y., Rosten, T.W., Henriksen, K., Hognes, E.S., Summerfelt, S., Vinci, B., 2016. Comparative economic performance and carbon footprint of two farming models for producing Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): land-based Closed containment system in freshwater and open net pen in seawater. Aquacult. Eng.71, 1-12.

International Organization for Standardization. (2006a). Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Principles and framework (ISO 14040:2006). ISO. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14040:ed-2:v1:en

International Organization for Standardization. (2006b). Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Requirements and guidelines (ISO 14044:2006). ISO.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press.

International Organization for Standardization. (2018). Greenhouse gases — Carbon footprint of products — Requirements and guidelines for quantification (ISO 14067:2018). ISO. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14067:ed-1:v1:en

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896

Robb, D.H.F., MacLeod, M., Hasan, M.R., Soto, D., 2017. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Aquaculture: A Life Cycle Assessment of Three Asian Systems. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 609,, Rome.

Rong, F., Liu, H., Zhu, J., Qin, G. (2025). Carbon footprint of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) cultured in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 510, 145606.

Sun,Y., Hou, H., Dong, D.,Zhang, J., Yang,X., Li, X., Song, X., (2023). Comparative life cycle assessment of whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) cultured in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), biofloc Technology (BFT) and higher-place ponds (HPP) farming systems in China. Aquaculture, 574, 739625.

Wiedmann, T., Minx, J., 2008. A definition of ‘carbon footprint’. In: Pertsova, C.C. (Ed.), Ecological Economics Research Trends. Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge (NY, USA), pp. 1-11.

World Resources Institute, & World Business Council for Sustainable Development. (2011). GHG Protocol Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard. Washington, DC: WRI and WBCSD.

WKC Group. (2023). PAS 2050: Assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services. WKC Group. https://www.wkcgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/PAS-2050-Assessment-of-the-life-cycle-greenhouse-gas-emissions-of-goods-and-services.pdf

Yang, L., An, D., Cui, Y., Jia, X., Yang, D., Li, W., Wang, Y.,Wu, L., (2024). Carbon footprint of fresh sea cucumbers in China: Comparison of three aquaculture Technologies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 469, 143249.