Module 9: Aquaponic System as A Sustainable Model

Summary / Description Text

This module discusses aquaponic systems and their importance in sustainable production. Aquaponics is an integrated production system that combines fish farming (aquaculture) with plant production (hydroponics). The system is based on the principle of converting fish waste into nutrients for plants through bacteria. In this way, water resources are used efficiently while also providing an environmentally friendly solution for waste management.

The module also explains the advantages of aquaponic systems (water savings, dual production, reduced need for chemical fertilizers) and their limitations (high installation costs, technical knowledge requirements, energy consumption). Different system types (media bed, nutrient film technique, deep water culture) are introduced and their application areas compared.

Keywords: aquaponics, integrated production, water conservation, circular economy, sustainable production, nutrient cycling, hydroponics.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module, participants will be able to:

• Explain the basic principles of aquaponic systems.

• Identify the environmental and economic advantages of aquaponic systems.

• Compare different aquaponic techniques (media bed, NFT, DWC).

• Evaluate the importance of aquaponic systems in terms of water conservation and waste management.

• Interpret the relationship of aquaponic systems with sustainable agriculture and aquaculture policies.

Presentation File

3. AQUAPONIC SYSTEM AS A SUSTAINABLE MODEL

3.1. Aquaponic Systems

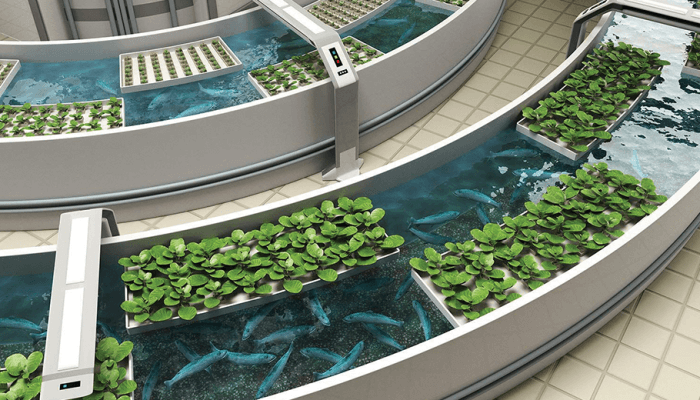

Aquaponics is an innovative and sustainable food production technology that combines aquaculture (fish farming) and hydroponics (soilless plant cultivation) (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). The system is based on the symbiotic relationship between fish and plants. Aquaponic systems consist of two main parts: the aquaculture section, where fish are raised, and the hydroponic section, where plants are cultivated (Bingöl, 2009). The nutrients in fish waste naturally fertilize the plants, while the plants use these nutrients to act as a filter, purifying the water for the fish (Meyer et al., 2025). The filtered water then returns to the fish tanks, contributing to a healthy living environment for the fish.

Aquaponic systems offer environmental and economic benefits such as water reuse, the cultivation of aquatic products in water-scarce areas, the reduction of chemical fertilizer use that may pose health risks to consumers, and increased efficiency in both fish and plant production (Meyer et al., 2025). This method represents an environmentally friendly approach to sustainable agriculture and water management. Figure 1 presents an example of an aquaponic system.

Figure 1. Example of an Aquaponic System (Turkish Agriculture and Forestry Journal, 2023).

In aquaponic systems, the nutrients present in wastewater are recovered through their uptake by plants. Microorganisms are also required in these systems to facilitate the transformation of wastes originating from fish and feed. In aquaponic systems, bacteria carry out the nitrogen cycle. In order to convert nitrogen into a form usable by plants, nitrification bacteria transform ammonia into nitrite and then nitrite into nitrate. Because dissolved substances are filtered by plants in aquaponic systems, the need for additional biological and chemical filtration is reduced (Yavuzcan Yıldız & Pulatsü, 2022). Figure 2 schematically illustrates the aquaponic system cycle.

Figure 2. Aquaponic system cycle

3.1.1. System Introduction

Aquaponic systems can be implemented at different scales depending on preferences and objectives. There are various systems such as home-based hobby systems, commercial-scale systems, and educational systems. The types of aquaponic systems also vary depending on the type of growing bed used. The main types of aquaponic systems are raft (deep water culture) systems, media-filled grow beds, nutrient film technique (NFT), wick systems, and drip systems (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018).

Fish species selection is highly important for aquaponic systems. Freshwater fish, in particular, are widely preferred in these systems. While species such as tilapia, koi, and carp are commonly chosen, other species produced in aquaponic systems include cod, white seabass, golden seabass, trout, Atlantic salmon, freshwater bass, and rainbow trout (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018; İzci et al., 2020). Various plant species are also cultivated in aquaponic systems. Green leafy vegetables such as lettuce, basil, mint, and arugula, as well as some varieties of tomatoes and peppers, are commonly grown plant species (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). In these systems, it is crucial to properly regulate water flow to ensure that plants receive sufficient oxygen.

Regular monitoring of water quality in aquaponic systems is critically important for maintaining fish health and ensuring the efficient operation of the system. In this context, parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate levels should be kept within appropriate ranges. The pH level in aquaponic systems is generally recommended to be between 6.8 and 7.0. This range is also crucial for the realization of nitrification (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). Table 1 presents the optimum values of temperature, pH, ammonium, nitrite, nitrate, and oxygen parameters for fish, plants, and bacteria, which are the main components of aquaponic systems (Şekeroğlu et al., 2022).

Table 1. Aquaponic System Conditions (Şekeroğlu et al., 2022)

| Organism | Temperature (°C) | pH | Ammonium (mg/L) | Nitrite (mg/L) | Nitrate (mg/L) | Oxygen (mg/L) |

| Warm-water Fish | 22-32 | 6-8,5 | <3 | <1 | <400 | 4-6 |

| Cold-water Fish | 10-18 | 6-8,5 | <1 | <0,1 | <400 | 6-8 |

| Plants | 16-30 | 5,5-7,5 | <30 | <1 | >3 | |

| Bacteria | 14-34 | 6-8,5 | <3 | <1 | 4-8 |

3.1.1.1. Raft System (Deep Water Culture Technique)

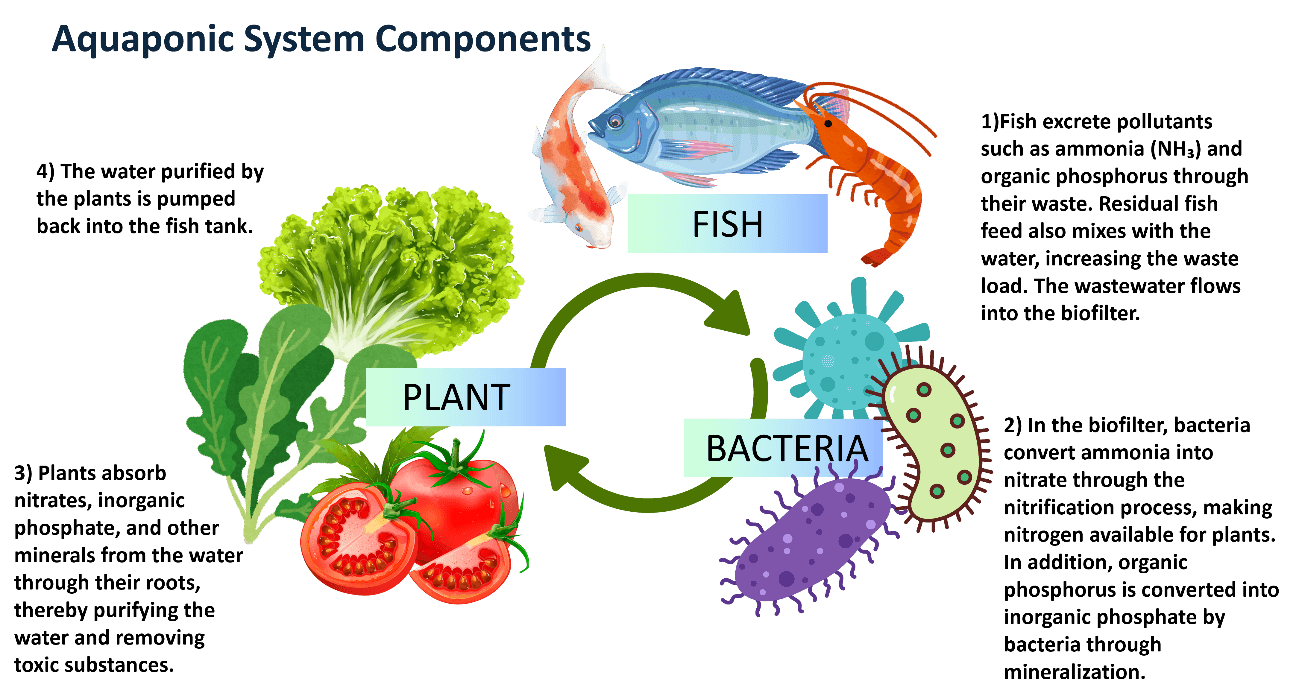

In this system, plants are placed on polystyrene (styrofoam) sheets, and it is also referred to as a floating system (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). In this method, water is pumped from the fish tank to the plants and the filtration system; as the water passes through the plant bed, it is cleaned and then recirculated back to the fish tank (Şekeroğlu et al., 2022). An example of a raft system is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Example of a Raft System (Gökvardar, 2013)

3.1.1.2. Nutrient Film Technique (NFT)

The nutrient film technique (NFT), also known as nutrient film system, is based on the principle of plant roots coming into contact with a thin layer of water flowing along the surface of a PVC channel or gutter, allowing simultaneous exposure to both air and water (Pattillo, 2017). In the system, the water flowing along the channel delivers the oxygen and nutrients required by the plants to their roots, and the water is filtered by the plants. The filtered water then flows back to the fish tank. Due to the lack of sufficient area for beneficial bacteria to live in this system, an additional biological filter is required (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). Figure 4 shows an example of an aquaponic system implemented using the nutrient film technique.

Figure 4. Example of an Aquaponic System Using the Nutrient Film Technique (Pattilo, 2017)

There are various studies examining the system dynamics of aquaponic systems established using the nutrient film technique (İzci et al., 2020; Prastowo et al., 2024). In the study conducted by İzci et al. (2020), the aquaponic system consisted of a fish tank containing Nile tilapia and a hydroponic unit with mint plants placed into holes drilled in PVC pipes. In this system, water from the aquarium was conveyed to the PVC pipes, reaching the plant roots, where biological filtration of nutrients in the wastewater took place. This process allowed for both plant growth and water purification. In the study, measurements such as growth performance and feed efficiency of the produced fish were carried out. The water’s pH, oxygen, and temperature were monitored daily, and weekly water samples were analyzed for NH₄, NO₂, NO₃, and PO₄ values. At the end of the 30–35 day trial period, the total length and weight of plants reaching harvestable size were compared with their initial length and weight to observe their growth. According to the results, the average pH during the trial was measured at 6.65 mg/L, with a minimum water temperature of 24.5 °C and a maximum of 26.8 °C. The oxygen level in the system was initially 7.25 mg/L in water not yet contaminated by feed waste, but variations in oxygen levels were observed as the water became polluted with fish and feed waste. The analysis of growth parameters showed a near 100% survival and growth rate in the fish used, while the plants also achieved rapid growth in a short period of time (İzci et al., 2020). The data obtained from the study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of the Aquaponic System Study Conducted by İzci et al. (2020)

| Category | Content |

| System Components | Fish tank (Nile Tilapia), PVC pipes, hydroponic unit (mint plants) |

| Water Cycle | Water from aquarium → PVC pipes → Plant roots (biological filtration) |

| Measured Parameters (Daily) | pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature |

| Measured Parameters (Weekly) | NH₄, NO₂, NO₃, PO₄³⁻ |

| Observation Period | 30–35 days |

| Plant Growth | Comparison of initial length and weight ↔ harvest length and weight (rapid growth in a short time) |

| Fish Growth | Growth performance, feed efficiency, nearly 100% survival rate |

| Results | Average pH: 6.65; Temperature: 24.5 °C–26.8 °C; During the first 3 days oxygen level was 7.25 mg/L; fluctuations in oxygen observed later as waste increased. |

| General Findings | High survival and growth rate in fish; rapid plant growth observed in a short period. |

In the study conducted by Prastowo et al. (2024), the aquaponic system consisted of hydroponic units prepared according to the nutrient-film technique (NFT) with red onions, a filtration area containing physical and biological filters, and a fish tank with ornamental koi fish. Within the system, dissolved nutrients derived from feed residues and fish excreta were continuously delivered to the plant roots through pipes and pumps. In the study, samples were taken from the roots in the hydroponic section and from the water in the biofilter compartment for bacterial community analysis (Prastowo et al., 2024). According to the results, the plant root surfaces were predominantly colonized by the bacterial community Proteobacteria (76%), which is noted for its important roles in the nitrification process in soil and aquatic environments (Prastowo et al., 2024). In the biofilter compartment of the aquaponic system, the dominant bacterial community was Bacteroidota (71%). Within this community, the genera Flavobacterium (98%) and Cloacibacterium (91%) were observed. Flavobacterium is important for the degradation of complex organic matter, while Cloacibacterium significantly contributes to nitrogen cycling in aquatic waste environments (Wa´skiewicz et al., 2014; Eck et al., 2019). Table 3 summarizes the findings obtained from the study conducted by Prastowo et al. (2024).

Table 3. Summary of the Aquaponic System Study Conducted by Prastowo et al. (2024)

| Category | Content / Findings |

| System Components | Fish tank (ornamental koi), hydroponic unit (NFT – red onion), filtration area (physical + biological filter) |

| Nutrient Cycle | Dissolved nutrients from feed residues and fish excreta were continuously delivered to the plant roots via a pump. |

| Analysis Method | Microbial samples were taken from red onion roots and water samples from the biofilter section. A bacterial community analysis was conducted. |

| Bacterial Communities (Plant Roots) | Dominant group: Proteobacteria (76%) – Function: plays an important role in the nitrification process. |

| Bacterial Communities (Biofilter – Water Samples) | Dominant group: Bacteroidota (71%) – Notable genera: Flavobacterium (98%); plays a role in the degradation of complex organic matter. Cloacibacterium (91%); contributes to the nitrogen cycle. |

3.1.1.3. Media-Filled Grow Beds (Media Culture Technique)

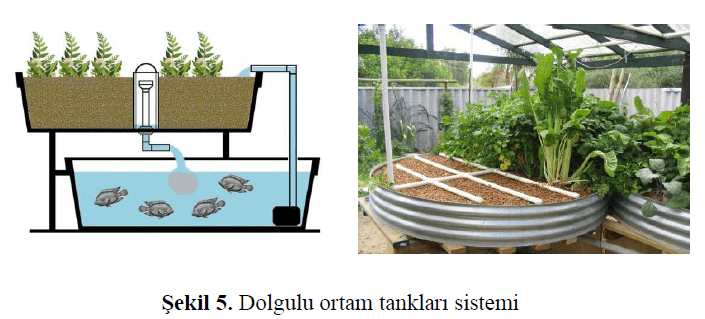

Hydroponic units are established by planting vegetation into tanks filled with filter media such as perlite or gravel, which act as biofilters (Şekeroğlu et al., 2022). The tanks containing the plants are periodically filled with water from the fish tank and then the water is returned back to the fish tank. Beneficial bacteria and sometimes worms are added to the plant tanks to facilitate the breakdown of waste (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). An example of this system is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Example of a Media-Filled Grow Bed System (Şekeroğlu et al., 2022)

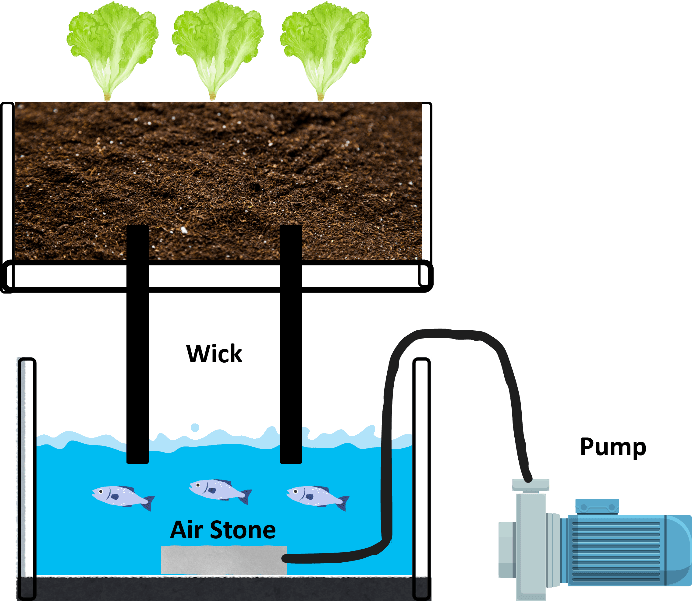

3.1.1.4. Wick System

The wick system is a small-scale system primarily established for hobby purposes, where water is absorbed through a wick-like absorbent material and transported to the plant roots (Gönen, 2013). Figure 6 shows an example of an aquaponic system using the wick method.

Figure 6. Example of Wick System

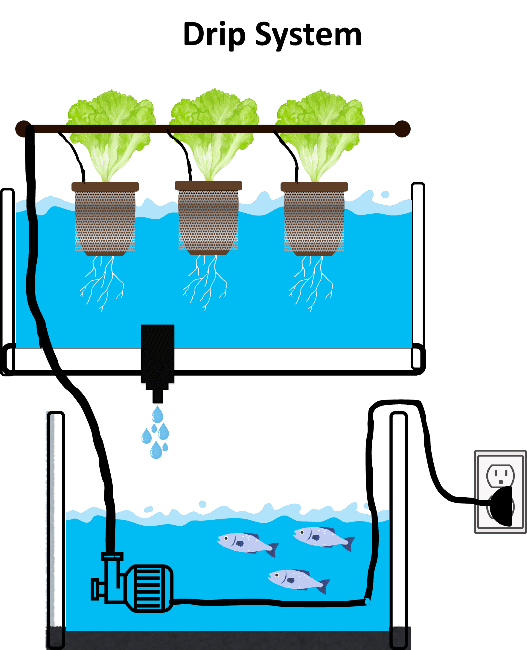

3.1.1.5. Drip System

In this system, aquaculture production is carried out using the drip irrigation method commonly applied in traditional agriculture (Gönen, 2013). An example of the drip system mechanism is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Drip system mechanism

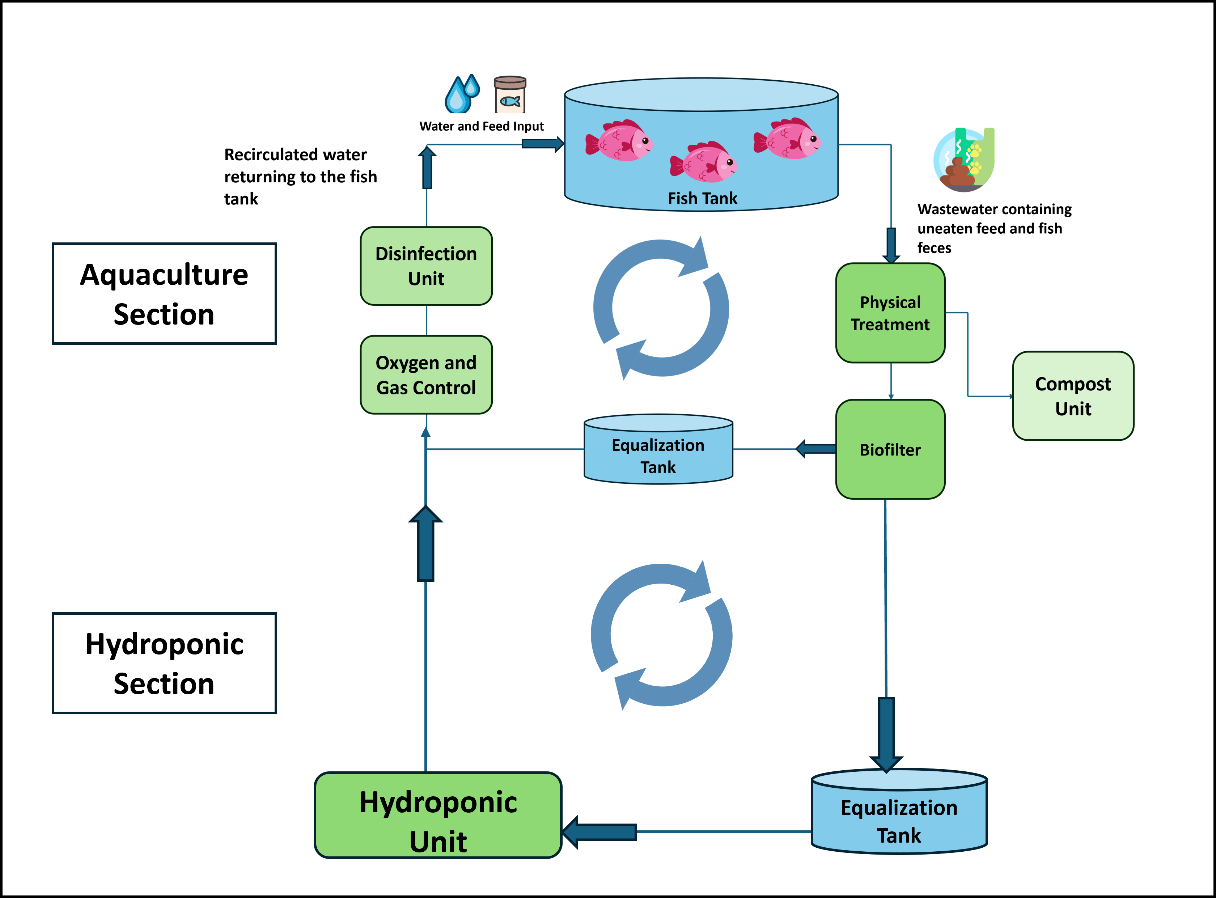

3.1.2. Hydroponic Systems

Hydroponic systems are a modern agricultural method in which plants are grown without soil, allowing their roots direct access to essential elements through a nutrient solution (Palm et al., 2019). Depending on the presence or absence of a solid medium that nourishes the plant roots, hydroponic systems are classified into two production techniques: aggregate systems and liquid systems (Bingöl, 2019). In these systems, water, oxygen, and nutrient elements required for plant growth are delivered in a controlled manner to the root zone.

Commonly used methods in hydroponic farming include the “Nutrient Film Technique (NFT),” where the nutrient solution is delivered to the roots as a thin film layer through channels with a depth of 1–2 cm; the “Deep Water Culture (DWC)” technique, where the roots are suspended over containers continuously filled with nutrient solution at a depth of 10–20 cm; and “Aeroponics,” where the roots are nourished by a sprayed solution (Van Os et al., 2008). When a recirculating aquaculture system is integrated into hydroponics, it forms an aquaponic system (Maucieri et al., 2019a). Figure 8 presents a schematic of an aquaponic system with its main units.

Figure 8. Units of an Aquaponic System

3.1.3. Historical Development of Aquaponic Systems

The earliest examples of aquaponic systems were implemented by the Aztec civilization, known as “Chinampa”, where plants were cultivated on fixed artificial islets and canals (Fernández et al., 2015). In later periods, the polyculture technique was applied in various Far Eastern countries, combining rice cultivation and fish culture in paddy fields (Kuşlu & Er, 2022). In subsequent years, at the New Alchemy Institute, ideas emerged to use fish waste as a fertilizer source for plants within the framework of wastewater management through plant production, and studies were conducted on these concepts (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018).

In the 1970s, academic studies on aquaponic systems began to expand knowledge in this field. In this context, in 1974, issues 2 and 3 of The Journal of New Alchemists published two articles by William McLarney entitled “Watering Garden Plants with the Productive Waters of Fish Ponds” and “Experiments on Watering Garden Plants with the Productive Waters of Fish Ponds” (Kargın & Bilgüven, 2018). The 1990s marked the years when the aquaponic technique became more widely covered in academic sources (Tokunaga et al., 2015). Figure 9 shows the first examples of aquaponic systems (Nelson, 2008).

Figure 9. Example of aquaponic cultivation by the Aztecs (Nelson, 2008; Kuşlu & Er, 2022)

3.1.4. Advantages and Disadvantages of Aquaponic Systems

Aquaponic systems, as a production method that enables the cultivation of multiple species simultaneously, offer significant advantages such as rapid, efficient, and resource-saving production, reduction of environmental impacts, food security, and economic savings (Bingöl, 2019; Hu et al., 2015).

In aquaponic systems, since the waste products decomposed by bacteria are used as a fertilizer source, nutrients are recovered from fish feed instead of chemically synthesized fertilizers used in hydroponic systems (Joyce et al., 2019a).

Thus, while effective waste management is achieved, production costs associated with fertilizer use are minimized.

Although aquaponic systems have many advantages, they also have some disadvantages such as the high cost of system installation, the need for technical knowledge for setup and operation, and the requirement for enclosed spaces (Bingöl, 2019). In addition, the need for high water quality in plant production within hydroponic units is another disadvantage (Maucieri et al., 2019b).

3.2. Environmental Management in Aquaculture Production

3.2.1. Ecological Processes in Aquaponic Systems

In aquaponic systems, compounds containing carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus released from waste are transformed into useful forms through ecological processes. In this context, pollutants such as ammonia (NH₃), organic phosphorus, and organic carbon originating from fish feces and uneaten feed are discharged into the system. According to the literature, fish feed typically contains 6–8% organic nitrogen, 1.2% organic phosphorus, and 40–45% organic carbon (Timmons & Ebeling, 2010).

In these systems, the recovery of waste through ecological processes such as the nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon cycles is achieved. Wastewater generated in aquaculture tanks flows into the biofilter. In the biofilter, bacteria convert ammonia into nitrate through the nitrification process, making nitrogen available for plants (Kim et al., 2005). In addition, organic phosphorus is converted into inorganic phosphate by bacteria through mineralization (Kim et al., 2024). Plants take up nitrates, inorganic phosphate, and other minerals from the water through their roots, thereby purifying the water and removing ammonia and nitrite, which are toxic to fish. The water purified by plants is then pumped back into the fish tank.

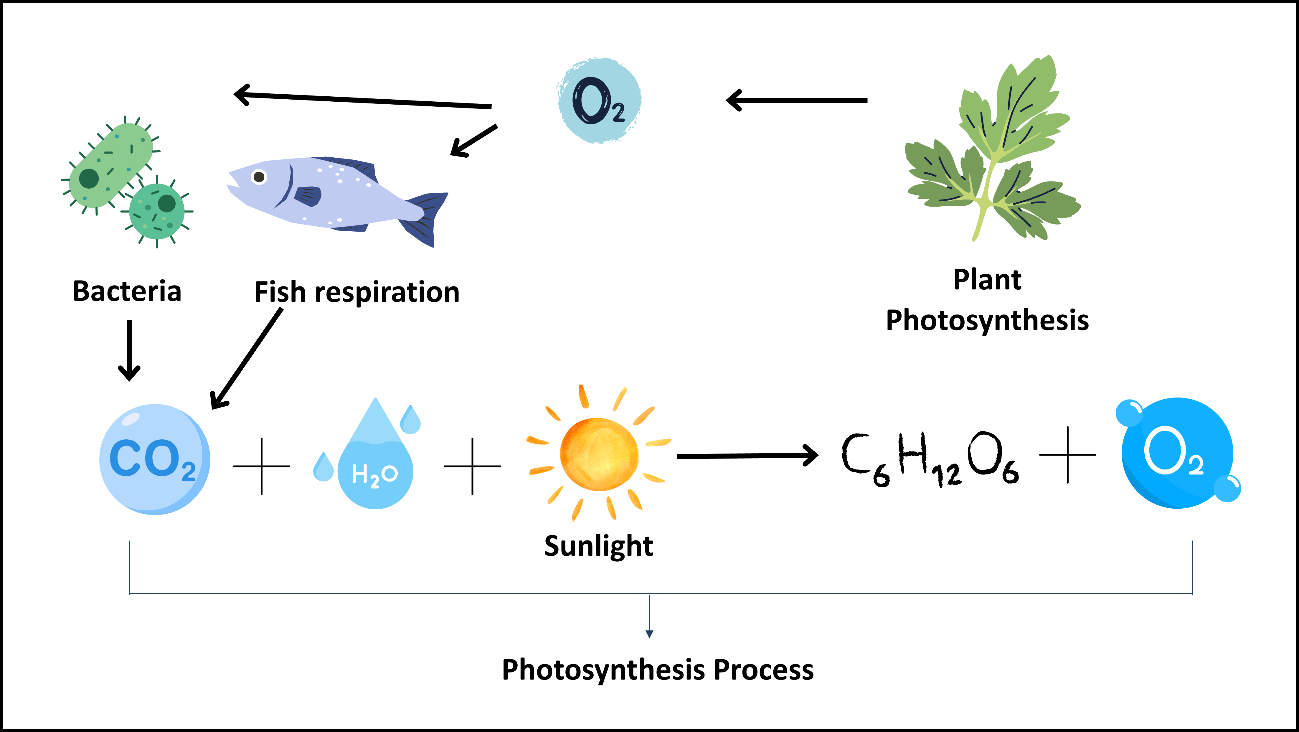

3.2.1.1.Carbon Cycle

In aquaculture systems, carbon dioxide (CO₂) is released as a result of the heterotrophic respiration of fish and bacteria (Espinal & Matulić, 2019). While fish release CO₂ through respiration, heterotrophic bacteria also produce CO₂ during the processes of breaking down organic matter and generating energy, while simultaneously consuming dissolved oxygen. In recirculating aquaculture systems, the stripping process is carried out to remove CO₂ from the water by bringing it into contact with large volumes of low-CO₂ air (Summerfelt, 2003).

In aquaponic systems, plants use the CO₂ released by fish and bacteria through photosynthesis, producing oxygen (O₂) in return, thus maintaining balance within the system (Friendly Aquaponics, 2023). This oxygen is essential for the survival of both fish and bacteria. In this way, a continuous carbon–oxygen exchange takes place between fish, bacteria, and plants, creating an ecological balance within the system. Figure 10 shows the carbon cycle occurring in aquaponic systems.

Figure 10. Carbon cycle in an aquaponic system

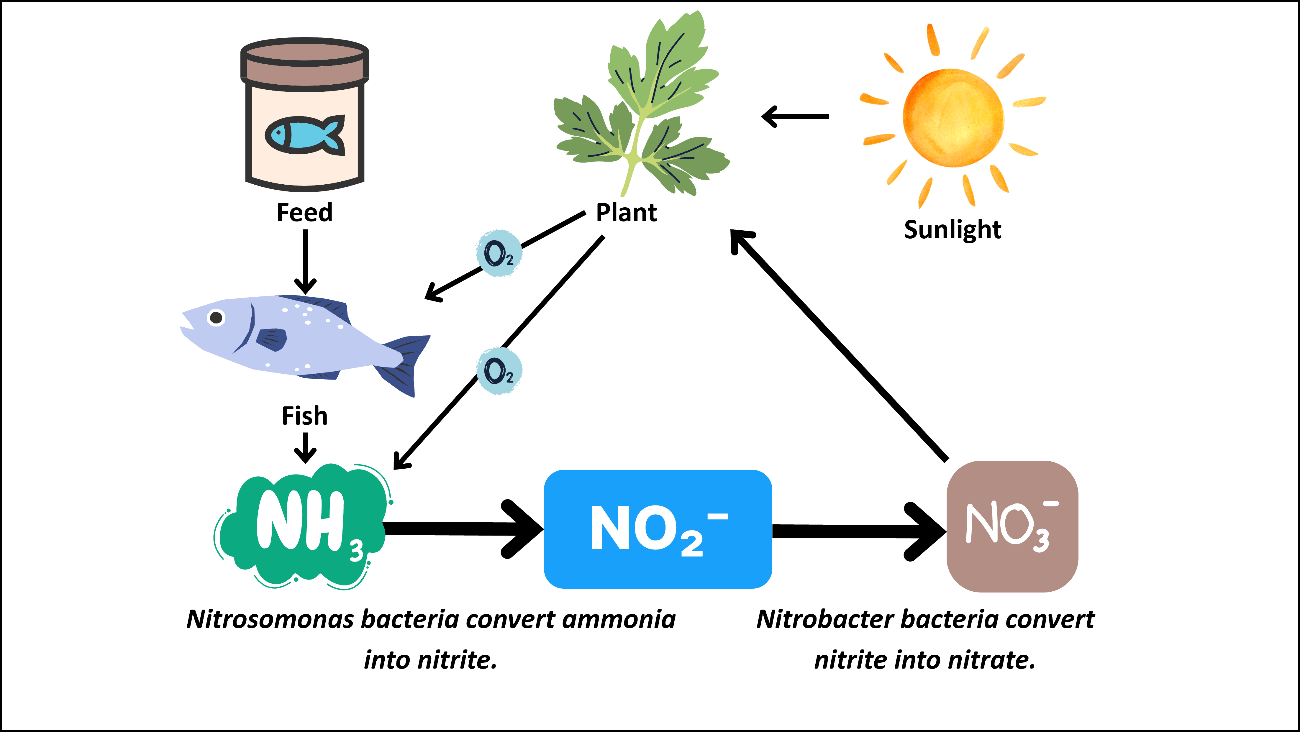

3.2.1.2.Nitrogen Cycle

The nitrogen cycle is highly important for the continuity and efficient operation of aquaponic systems (Bingöl, 2019). In aquaponic systems, plants and bacteria actively play a role in the nitrogen cycle. The primary sources of nitrogen in aquaponics are fish excreta and nitrogen-rich feed residues. After fish consume the feed, nitrogenous wastes are released in the form of ammonia (NH₃/NH₄⁺). Since this ammonia is toxic to fish, the role of bacteria becomes critical in the cycle. Nitrifying bacteria (such as Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter species) convert ammonia first into nitrite (NO₂⁻) and then into nitrate (NO₃⁻) (Kim et al., 2005). Nitrate is a non-toxic form of nitrogen that can be easily absorbed by plants. Thus, while bacteria transform harmful nitrogen compounds into a safe nutrient, plants take up this nitrate through their roots for growth, simultaneously purifying the water and creating a healthy living environment for the fish. Figure 11 summarizes the nitrogen cycle occurring in aquaponic systems.

Figure 11. Nitrogen cycle in aquaponic systems

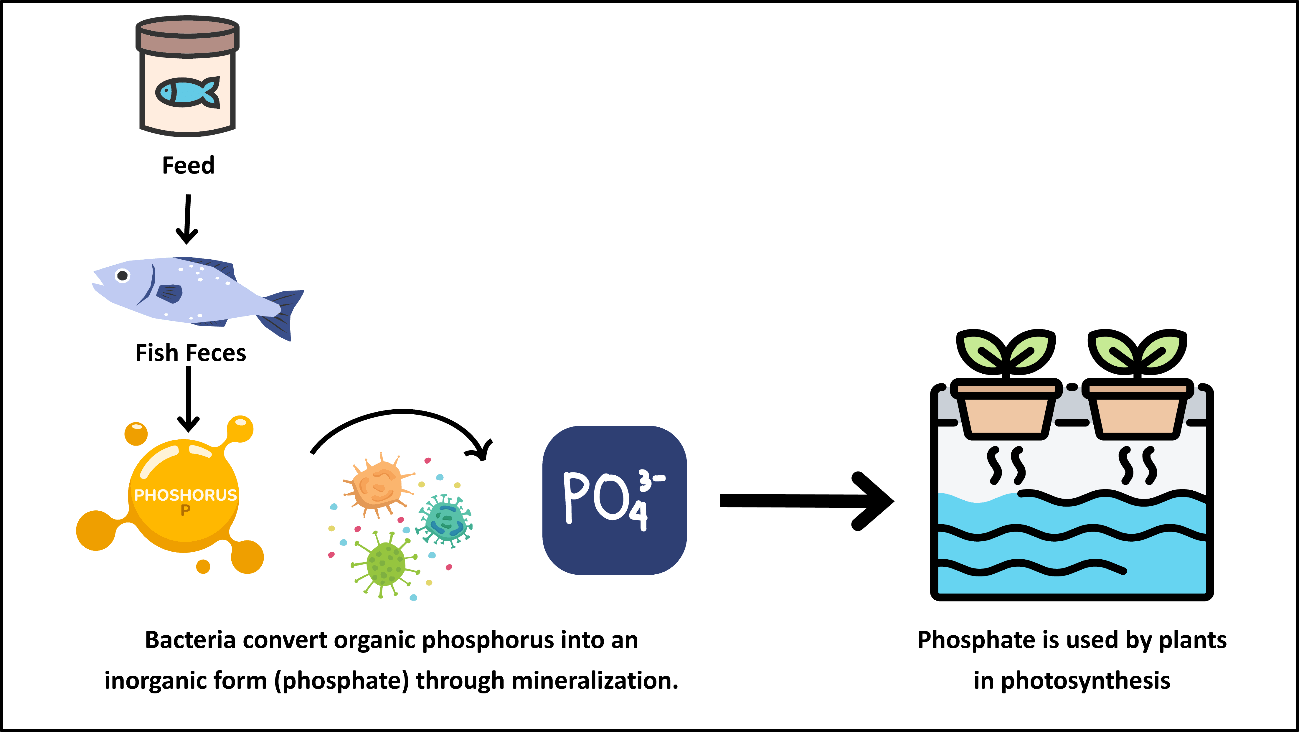

3.2.1.3. Phosphorus Cycle

In aquaponic systems, phosphorus, like other minerals, is primarily introduced through fish feed and excreted via fish metabolism. However, the phosphorus released into the environment is mostly in organic forms, and therefore it must be converted into inorganic phosphate form to be directly available for plant uptake (Becquer et al., 2014). At this point, heterotrophic bacteria in the system convert organic phosphorus into inorganic phosphate (PO₄³⁻) through the process of mineralization (Joyce et al., 2019b). This conversion makes phosphorus available for plants, enabling its effective utilization in root development, energy metabolism (ATP production), and photosynthesis. However, excessive accumulation of phosphorus in the system can lead to algal growth and water quality issues, which is why plant uptake of phosphorus is crucial for maintaining the ecological balance of the cycle.Recovering phosphorus in a plant-available form within aquaponic systems reduces the need for supplemental phosphorus ,the second most important macronutrient after nitrogen, thereby contributing to resource savings in production (Joyce et al., 2019b). Figure 12 shows the schematic representation of the phosphorus cycle in aquaponic systems.

Figure 12. Phosphorus Cycle in Aquaponic Systems

Eck, M. Sare, A.R. Massart, S. Schmautz, Z. Junge, R. Smits, T.H.M. Jijakli, M.H. 2019, Exploring bacterial communities in aquaponic systems, Water (Switzerland) 11 (2) https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020260.

Espinal, C.A. & Matulić, D. 2019. Recirculating Aquaculture Technologies. In: Goddek, S., Joyce, A., Kotzen, B., Burnell, G.M. (Eds.), Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 35-76.

Becquer A, Trap J, Irshad U, Ali MA, Claude P (2014) From soil to plant, the journey of P through trophic relationships and ectomycorrhizal association. Front Plant Sci 5:548

Bingöl, B. 2019. Alternatif Tarım Yöntemleri; Aeroponik, Akuaponik, Hidroponik. Harman Time Dergisi, Aralık/2019, 7(82), 34-42, ISSN: 2147-6004.

Fernández Cañero, R., L. Pérez Urrestarazu and G. Egea Cegarra (2015). Design and preliminary assessment of a vertical aquaponics system for ornamental purposes. International Conference on Living Walls and Ecosystems Services (2015), p 1-41.

Friendly Aquaponics. (2023). Carbon dioxide (CO₂) vs. dissolved oxygen (DO). Friendly Aquaponics. https://friendlyaquaponics.com/aquaponics-terms-easily-confused-carbon-dioxide-co2-vs-dissolved-oxygen-do/#:~:text=Carbon%20dioxide%20is%20essential%20for,gasses%20for%20optimal%20system%20performance.

Gökvardar, A. 2013. Kapalı Devre Sistemlerde Akuaponik Uygulamaları: Deniz Balıkları-Bitkisel Üretim Entegrasyonun Araştırılması. Ege Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Su Ürünleri Yetiştiriciliği Anabilim Dalı, Yüksek Lisans Tezi, İzmir.

Gönen, S. (2013). Akuaponik Bahçecilik ve Akuaponik Sistemlerin Yaşayan Elementleri: Solucanlar. (http://solucangubresi.web.tr/makaleler/makaleler-2/akuaponik-bahcecilik-ve-akuaponiksistemlerin-yasayan-elementlerisolucanlar)

Hu, Z., Lee, J. W., Chandran, K., Kim, S., Brotto, A. C. and Khanal, S. K., 2015. Effect of plant species on nitrogen recovery in aquaponics. Bioresource Technology.

İzci, B., Selek, M., Berber, S. 2020. AKUAPONİK SİSTEMDE NİL TİLAPİA (Oreochromis niloticus ) VE NANE (Mentha piperita) YETİŞTİRİCİLİĞİ. Menba Kastamonu Üniversitesi Su Ürünleri Fakültesi Dergisi, 6(1): 30-36

Joyce, A., Goddek, S., Kotzen, B., Wuertz, S., 2019a. Aquaponics: closing the cycle on limited water, land and nutrient resources. In: Goddek, S., Joyce, A., Kotzen, B., Burnell, G.M. (Eds.), Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6_2, 978- 3-030-15943-6.

Joyce, A., Timmons, M., Goddek, S., Pentz, T., 2019b. Bacterial Relationships in Aquaponics: New Research Directions. In: Goddek, S., Joyce, A., Kotzen, B., Burnell, G.M. (Eds.), Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 145-161. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6_2, 978- 3-030-15943-6.

Kargın, H., & Bilgüven, M. 2018. Akuakültürde Akuaponik Sistemler ve Önemi. Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 32(2), 159-173.

Kim, D.-J., Ahn, D.H., Lee, D.-I., 2005. Effects of free ammonia and dissolved oxygen on nitrification and nitrite accumulation in a biofilm airlift reactor. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 22, 85–90.

Kim, H.-J., Guerrero González, M. de la L., Quintero-Castellanos, M. F., Delgado-Sánchez, P., & et al. (2024). Isolation and identification of Lysinibacillus sp. and its effects on solid waste as a phytate-mineralizing bacterium in an aquaponics system. Horticulturae, 10(5), 497. https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/10/5/497

Kuşlu, Y., & Er, H. (2021). Akuaponik tarım sistemleri. In K. Kökten & H. İnci (Eds.), Tarım ve hayvancılığın sürdürülebilirlik dinamikleri üzerine akademik çalışmalar (ss. 71–89). İKSAD Yayınevi.

Maucieri, C., Nicoletto, C., Zanin, G., Birolo, M., Trocino, A., Sambo, P., Borin, M., Xiccato, G. (2019a) Effect of stocking density of fish on water quality and Growth performance of European Carp and leafy vegetables in a low-tech aquaponic system. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0217561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217561

Maucieri, C., Nicoletto, C., Van Os, E., Anseeuw, D., Van Havermaet, R., Junge, R. 2019b. Hydroponic Technologies. In: Goddek, S., Joyce, A., Kotzen, B., Burnell, G.M. (Eds.), Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 77-110. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6_2, 978- 3-030-15943-6.

Meyer, J., Weisstein, F.L., Kershaw, J., Neves, K. 2025. A multi-method approach to assessing consumer acceptance of sustainable aquaponics. Aquaculture, 596, 741764, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741764

Nelson, R., 2008, Aquaponic Food Production: Raising Fish and Plants For Food and Profit, Published by Nelson and Pade, Inc., USA.

Palm, H. W., Knaus, U., Appelbaum, S., Strauch, S. M., & Kotzen, B. (2019). Coupled aquaponics systems. In S. Goddek, A. Joyce, B. Kotzen, & G. M. Burnell (Eds.), Aquaponics food production systems (pp. 163–200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15943-6_7

Pattillo, D.A. 2017. An Overview of Aquaponic Systems: Hydroponic Components. North Central Regional Aquaculture Center, https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/handle/20.500.12876/55937

Prastowo, B.W., Lestari, I.P., Agustini, N.W.S, Priadi, D., Haryati, Y., Jufri, A., Deswina, P. Adi, E.B.M., Zulkarnaen,I., 2024. Bacterial communities in aquaponic systems: Insights from red onion hydroponics and koi biological filters, Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 10, 100968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2024.100968.

Summerfelt ST (2003) Ozonation and UV irradiation – An introduction and examples of current applications. Aquac Eng 28:21–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S01448609(02)00069-9

Şekeroğlu, A., Kökten, K., & İnci, H. 2022. Tarım ve hayvancılığın sürdürülebilirlik dinamikleri üzerine akademik çalışmalar. Ankara: İKSAD Publishing House.

Timmons, M.B. & Ebeling, J.M. (2010). Recirculating Aquaculture, 2nd ed. NRAC Publication NO. 01-007. Cayuga Aqua Ventures, Ithaca, NY.

Tokunaga, K., Tamaru, C., Ako, H. and Leung, P., 2015. Economics of Smallscale Commercial Aquaponics in Hawaii. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 46; 20-32.

Turkish Agriculture and Forestry Journal -Türk Tarım Orman Dergisi. (2023, Ekim 26). Akuaponik üretimle balık ve sebze bir arada yetişiyor. http://www.turktarim.gov.tr/Haber/976/akuaponik-uretimle-balik-ve-sebze-bir-arada-yetisiyor

Van Os EA, Gieling TH, Lieth JH (2008) Technical equipment in soilless production systems. In:Raviv, Lieth (eds) Soilless culture, theory and practice. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 157–207.

Waśkiewicz, A., & Irzykowska, L. (2014). Flavobacterium spp. – Characteristics, Occurrence, and Toxicity. Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology, 938–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384730-0.00126-9

Yavuzcan Yıldız, H., & Pulatsü, S. 2022. Towards zero waste: sustainable waste management in aquaculture. Ege Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 39(4), 341-348. DOI: 10.12714/egejfas.39.4.11